A forthcoming book by Larry Catá Backer

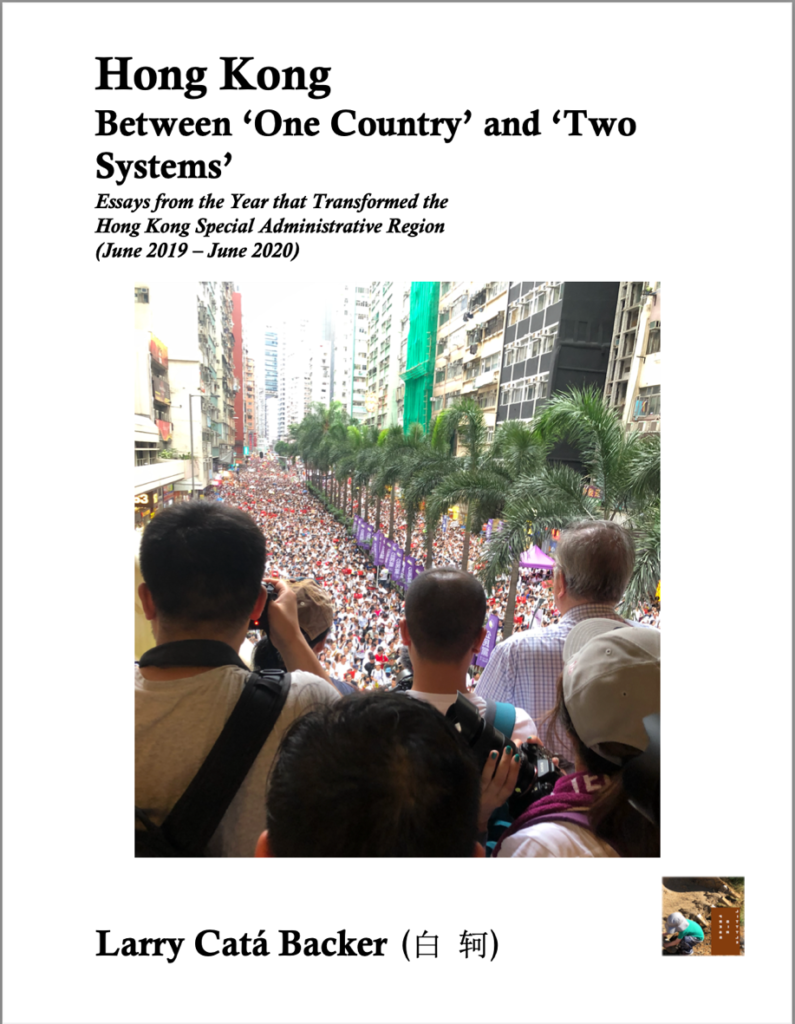

Hong Kong Between “One Country” and “Two Systems” examines the battle of ideas that started with the June 2019 anti-extradition law protests and ended with the enactment of the National Security and National Anthem Laws a year later. At the center of these battles was the “One Country, Two Systems” principle. By June 2020, the meaning of that principle was highly contested, with Chinese authorities taking decisive steps to implement their own understanding of the principle and its normative foundations, and the international community taking countermeasures. As events progressed between June 2019 and June 2020, the author devised a series of essays that analytically chronicle the discursive battles that were fought, won and lost. Without an underlying political or polemical agenda, the essays retain the freshness of the moment, reflecting the uncertainties of those times as events unfolded. What was won on the streets of Hong Kong from June to December 2019, namely, the public and physical manifestation of a principled internationalist and liberal democratic narrative of self-determination, and of civil and political rights, was lost by June 2020 within a cage of authoritative legality legitimated through the resurgence of the normative authority of the state and the application of a strong and coherent expression of the principled narrative of its Marxist-Leninist constitutional order. Ironically enough, both political ideologies emerged stronger and more coherent from the conflict, each now better prepared for the next one.

The essays written between June 2019 and June 2020 are compiled in Hong Kong Between “One Country” and “Two Systems” with little change to how they were originally written. The book is presented as a diary with essays as diary entries. This is to mark an intellectual progression that matches the development of Hong Kong’s political turmoil. The object is to capture not just the strategic and normative developments that produced Hong Kong’s new order from June 2020, but also to give a sense of the uncertainties and anticipations that existed leading up that moment. The process of ideological genesis from June 2019 to June 2020 is most immediately captured from a state of anticipation without the benefit of foresight. It is that immediacy that adds a layer of analysis to the usual post facto accounting and examination of events. That layering, anyway, is the aim. The essays in Hong Kong Between “One Country” and “Two Systems”, then, do not look back on events after the fact, but speculate, discover, and capture moments that from June 2020 look inevitable but which from the perspective of June 2019 appeared far less so. By doing so the book aims to retain the freshness of the moment. It is, thus, both a journal of events, and a journey. For its readers it may serve as a record of how the way of thinking about the situation of Hong Kong changed radically over such a short period of time. It is also, in part, a chronicle of the way in which larger events—the US-China trade war, and the COVID19 pandemic—can have a substantial effect on what would otherwise be a localized affair.

The focus of the book is on discourse. The essays follow events as they unfolded through the rhetoric of the parties involved–their statements, their gestures, their performances on the streets, and ultimately the memorialization of these discourses in the landmark laws of the Hong Kong after June 2020–the National Anthem Law and the National Security Law. To some extent this discursive focus owes a debt to and might be comfortably embedded within analytic traditions that owe much to the insights of Guiguzi (鬼谷子) and its rhetoric,[1] which makes its appearance throughout the essays and perhaps binds them together into something more coherent. These insights frame some of the analysis, as do the insights of critical thinkers from the Western tradition.

Hong Kong Between “One Country” and “Two Systems” is organized into six parts. Part I (Epilogue as Introduction) starts at the end of the story. It uses a rare statement endorsed by a substantial majority of the representatives of the United Nations Human Rights special procedures calling for the development of decisive measures to protect human rights in the face of the enactment by Chinese authorities of the National Security Law for Hong Kong. This is to situate the story of Hong Kong between June 2019 and June 2020 from the perspective of the international community–perhaps among the actors most adversely affected by the story of Hong Kong.

Part II consists of eleven chapter essays. These essays take the reader from the beginning of the protests in June 2019 to the end of August 2019. The essays serve as an analytical witness to the development of the initial phase of the Hong Kong protests. Step by step, as it occurred, Part II considers the escalations of ambitions and tactics of the protesters, the growing intransigence of local officials, and the start of what would become an elaborate and largely effective counter position of the Chinese central authorities. Much of what occurred during these early weeks provided the foundation for everything that developed thereafter.

Part III consists of seven essays. The essays chronicle critical events taking place from the beginning of September to the end of November 2019. These take the reader through the next phase of development, one in which initial positions are fully developed and hardened. Here one sees fully developed the ideological position of the central authorities that in retrospect were faithfully memorialized in the National Anthem Law, the National Security Law, and recent amendments to the Election rules in the Hong Kong Basic Law in March 2021. At the same time, one encounters here the maturing of an aligned position of the various groups of protesters that sought to deepen the internationalization of their movement and preserve efforts to permanently protect a measure of liberal democratic order in Hong Kong. Lastly, the international response also developed in this period: grounded first in the narrow strictures of the Sino-British Joint Declaration and thereafter in general fundamental principles of self-determination and the international civil and political rights of coherent political communities.

Part IV then considers two stalemates. Firstly, three essays cover the relatively short period of stalemate between December 2019 and April 2020 which includes the apex of protester power in December 2019 and January 2020. Secondly, the stalemate imposed by the realities of the worldwide COVID-19 pandemic. One moves here from the unabated storm of protest to the opportunity that the pandemic provides local and national authorities to break the stalemate in their favor. It was during this period that the stakes around the proper conceptualization of the One Country Two Systems principle became clear. On one side were central authorities who now fully developed the construct of the principle as a means of permitting autonomy within the discretionary authority of the state. On the other were the protesters and the international community who now saw in One Country Two Systems a principle of divided sovereignty in which the political choices of the Hong Kong community could be protected against encroachment by the central authorities, one based on international liberal democratic and human rights principles.

Part V chronicles the end of the protest movement and the emergence of a “new” Hong Kong between May and July 2020. Its seven essays critically chronicle the way that the central authorities drove events from May 2020, in a way that paralleled how protesters drove events between June and September 2019. Part V starts with the announcement of an intention to impose the National Security Law, by first devising the National Anthem Law and then ending with the adoption of the National Security Law itself. The seven essays here consider the importance in developing a patriotic front as a means of dividing and managing the people of Hong Kong, and consider the relatively little opposition that the central authorities faced in realizing their objectives.

The single essay that makes up Part VI serves as the after-word of Hong Kong’s story. Part VI is meant not only to end the story of the protests in Hong Kong but also to begin the story of Hong Kong as a more integrated part of the Pearl River area of China. No longer an international city in the sense of being internationally recognized and having a protected legal autonomy from its territorial sovereign, Hong Kong now rejoins the nation as a Chinese city with substantial international connections. Beyond that, Hong Kong’s future is now far more closely aligned with that of the Chinese heartland and with the vision of China’s central authorities for the nation as a whole.

The publisher, Little Sir Press, will be hosting a book launch author meets reader webinar on 13 July 2021. Registration is required but free. Free chapters and more about Hong Kong Between ‘One Country’ and ‘Two Systems is available here.

Larry Catá Backer is the W. Richard and Mary Eshelman Faculty Scholar, Professor of Law and International Affairs at Pennsylvania State University (B.A. Brandeis University; M.P.P. Harvard University Kennedy School of Government; J.D. Columbia University). He researches in the areas of Marxist Leninist political-economic systems with a focus on China and Cuba, economic globalization, corporate social responsibility, international affairs, global governance, trade and finance, and semiotics. In addition to his own books, Backer has published over one hundred articles and book chapters in journals in the U.S., Latin Americas, China, and Europe. For a list of his publications, please click here. Backer also runs his own blog, Law at the End of the Day.

[1] Guiguzi (鬼谷子), Guiguzi: China’s First Treatise on Rhetoric; A Critical Translation and Commentary (Hui Wu (trans.); Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2016 (before 220 A.D.))