A new paper by Hannah Klöber

Born from an intention to establish a financial credit (investigation) system, the Social Credit System (SCS) is a mega-project to improve governance capabilities and legal compliance. However, the modern publicly run SCS resembles rather an interconnected set of initiatives under the umbrella term of creating “trust” than being a comprehensive system to monitor and rank all citizens. Currently, the basic components at the national level that are being created are the information infrastructure and the joint enforcement mechanism. Both components rest on the sharing among agencies and the general disclosure of compliance information on subjects, to on the one hand punish and educate, but also to facilitate assessing any entity’s “trustworthiness”. They constitute an emerging state-led data processing mechanisms which may strongly impact the lives of individuals, companies, social organizations and other actors throughout China, with the centrepiece being the information it holds about its subjects. Acknowledging the wide-reaching consequences that the contents of social credit information about a subject may have, this article (draft) asks: What legal framework do SCS builders create to guarantee the accuracy of personal social credit information?

Why is Personal Data Accuracy Important?

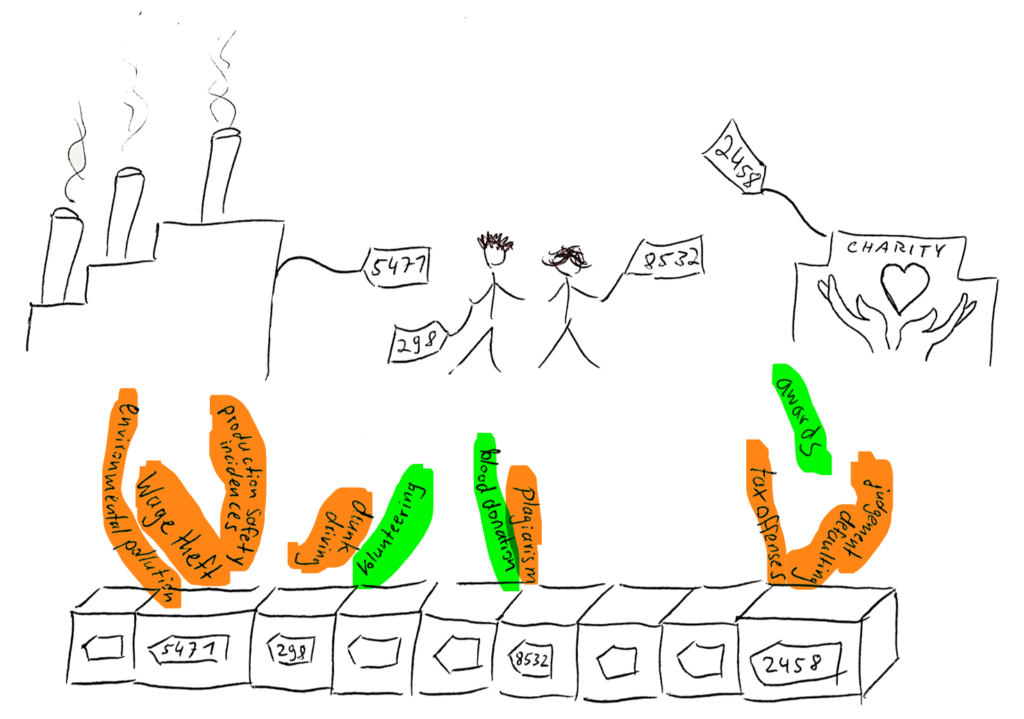

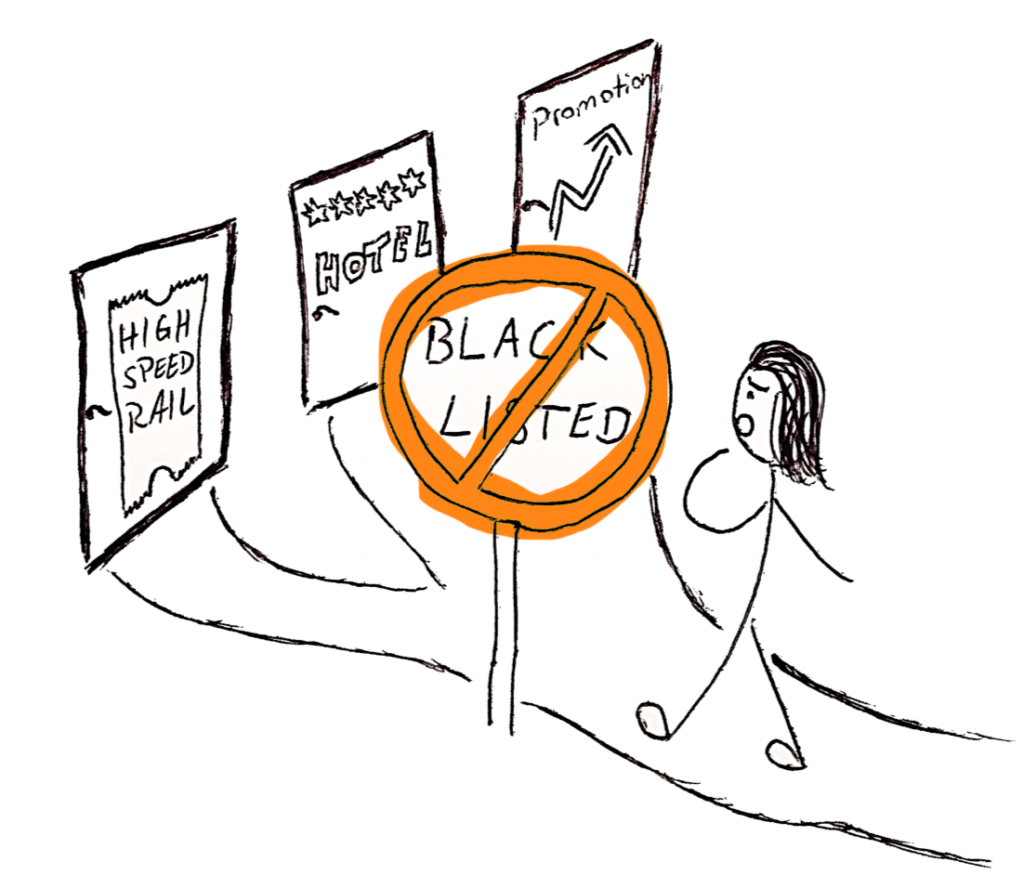

One area where social credit information is currently bringing about consequences for subjects is the joint enforcement mechanism – or “joint disciplining for trust-breaking”. The joint enforcement mechanism is mostly set up by State Council policy documents, promoting desired behaviours and discouraging unwanted ones through so-called blacklists and redlists. Listing might lead to punishment or benefits by unrelated actors (as redlists confer benefits, they are much less problematic and thus not discussed in detail). It has to be noted that the mechanism’s main focus rests on companies but there is a corporate overlap, as leading personnel can get blacklisted due to their company’s wrongdoings. So far, there is no real central management to these lists. For the purpose of analysing the legal aspects of joint enforcement, four stages must be differentiated: preparatory acts before blacklisting, the blacklisting decision, the publication of the blacklist and the ensuing disciplinary action. They can be based on the same facts and norms but may be executed by different actors and be linked together.

To achieve its goal of promoting trust and steering behaviour, the SCS needs large amounts of accurate data. Simultaneously, data inaccuracy in this behemoth of a reputational shaming machine could potentially harm a large number of people: Because open government data is intended to be reused, it is very hard to control once publicised. For example, if an entity is entered on one of the many blacklists for trust-breaking, she may find her name on display in public spaces as well as online platforms, screenshots of which may be further shared across social media. The inaccuracy discussed here encompasses only factual errors, thus instances where data is not correct, complete, or timely, resulting from inattentiveness during handling. Legal errors on the other hand concern the application of law (for example excessiveness of punishment) and are outside the scope of this study.

What Legislation is There?

The looseness of the concept of social credit and the plurality of actors involved make the regulatory situation quite complex. There is no national social credit law (although a draft for soliciting comments from the public has been published in November 2022), but a host of special sectoral and provincial regulations dealing with different social credit initiatives create a jumbled regulatory landscape. Apart from this, in the context of personal data accuracy national legislation such as the 2021 Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL) and the Regulation on Open Government Information (ROGI, revised in 2019) apply. Administrative legislation on procedural issues should be applicable, but the placement of joint enforcement measures under administrative law is still disputed.

What Does it Offer?

Basic Definitions

Generally, social credit is defined as the status of information subjects complying with legally prescribed obligations or performing contractual obligations in their social and economic activities (see e.g., Shanghai Municipal Social Credit Regulations art 2(1), Tianjin Municipal Social Credit Regulations art 2(2)), while social credit information is defined as (objective) data and materials that can be used to identify, analyse and judge the status of information subjects’ compliance with the law and contract performance (see e.g. Shanghai Municipal Social Credit Regulations art 2(2), Henan Provincial Social Credit Regulations art 3 (3)). What this means in detail remains unclear, though. Two types of social credit information exist: public credit information and non-public (or market) credit information, depending on the generating entity (state or private actor).

Accuracy Obligations for Data Processors

PIPL and ROGI provide some guidance on how to handle and publish government information, but data quality requirements are not sufficient for the complex processes of the SCS. The examined provincial documents either set up principles for the processing of public social credit data or impose data-quality responsibilities on information providers. The latter can also be found in sectoral regulation, but only in a third of the covered documents.

Notification Requirements

Because of the multi-actor structure of joint enforcement, credit subjects face the problem of recognizing the possibility of rights relief and identifying the right addressee for enforcing their rights. One important way to counteract this situation is notification requirements. The PIPL introduced a general notification obligation in 2021, covering among other things the processor’s name and contact information, and the methods and procedures for individuals to exercise their rights. But proper notification requirements are generally rare among special legislation documents. To best protect credit subjects, notification should occur at all four possible stages of joint enforcement. In the preparatory stage and after the listing decision they are however only seldom found. A few provincial documents provide for the notification of listing, but only for the so-called seriously untrustworthy lists, which cause stricter restrictions than normal blacklists. Some measures consider the publication of blacklists as a form of public notification. Notification of punishment is generally not covered by blacklist management documents, as the listing entity is usually not in charge of punishment. A quarter of the sectoral and most of the provincial documents do not set up any notification procedures.

Review Procedures Prior to Blacklisting

Among the analysed documents, procedures for prior review can be found only in those measures which also stipulate notification before inclusion. None of the norms provide for suspension, however. A clear classification of joint enforcement measures under administrative law would improve the situation, although there is no general administrative procedure law in China.

Access to One’s Personal Credit Information

General access rights are provided by both the PIPL and the ROGI. About half the provincial documents explicitly set up a right to inquire one’s own information. Other regulations appear to take accessibility for granted and only regulate the corresponding procedures for data providers.

Objection Procedures after Blacklisting

If personal information held by the government is found to be incorrect or incomplete, individuals have a general right to request correction under PIPL and ROGI. The content of specific objection procedures among the special legislation is uneven. Two models can be found in the analysed documents: objection to wrong information for a fixed time period after publication of the decision, or a general possibility of objection. In provincial documents, only the latter can be found, while some of the ministerial documents designate no objection possibilities at all. Generally, the stipulated handling time for objections in provincial documents is shorter than in the ministerial regulations, often calling for verification within a few days, rather than weeks. While the State Council calls for the suspension of enforcement during verification procedures, this is rare in implementing documents. On the contrary, some ministries and the SPC explicitly regulate that objection will not cause suspension or impact publication. A compromise, to mark objected information during verification procedures, is employed by almost two-thirds of the provincial documents. The deletion of non-verifiable data is not always required.

Dissemination of Corrected Data throughout the System(s)

The dissemination of corrected data is thinly regulated. Where it is mandated, it often merely requires that other providers of the information are informed. The information subject itself might only be informed of updates and corrections in its social credit information if the change is due to a successful objection the subject has initiated.

A Patchwork

The study finds that special legislation is inconsistent and that national legislation is often too vague to deal with the complicated and diverse processes of the SCS. Further legislation will be needed to standardise procedures. While it is often difficult for data subjects to exercise their rights against first-party collectors, when raised against third party-reusers of data, the problem multiplies. Special legislation by different national actors and local legislators is very diverse, and procedural requirements are often vague, fragmented or missing. Some regulations deviate from protection measures proposed in policy documents. The rules in the examined documents range from almost no regulation to some very promising models in the eastern, economically more developed provinces. The biggest issue remains a lack of solid ex ante control mechanisms, as most relief is only provided after the fact. This is problematic, as the spread of inaccurate data can cause unforeseen consequences, and reputational damage is difficult to repair.

The article The Regulation of Personal Data Accuracy in China’s Public Social Credit System was published in the Hong Kong Law Journal (2023, Vol. 53, No. 1). A free draft is available here.

Hannah Klöber is a Research Assistant at University of Cologne, where she is currently working on her PhD with the Chair for Chinese Legal Culture. Her dissertation deals with the Proportionality Principle in Chinese administrative law, examining it from a comparative perspective, exploring its application by and use for Chinese actors, thereby gaining deeper insight into its function, potential and limitations. She holds a BA and MA in Chinese Regional Studies, Law from Cologne University. She can be contacted at hkloeber[at]smail.uni-koeln.de