A new paper by Michael Bohlander

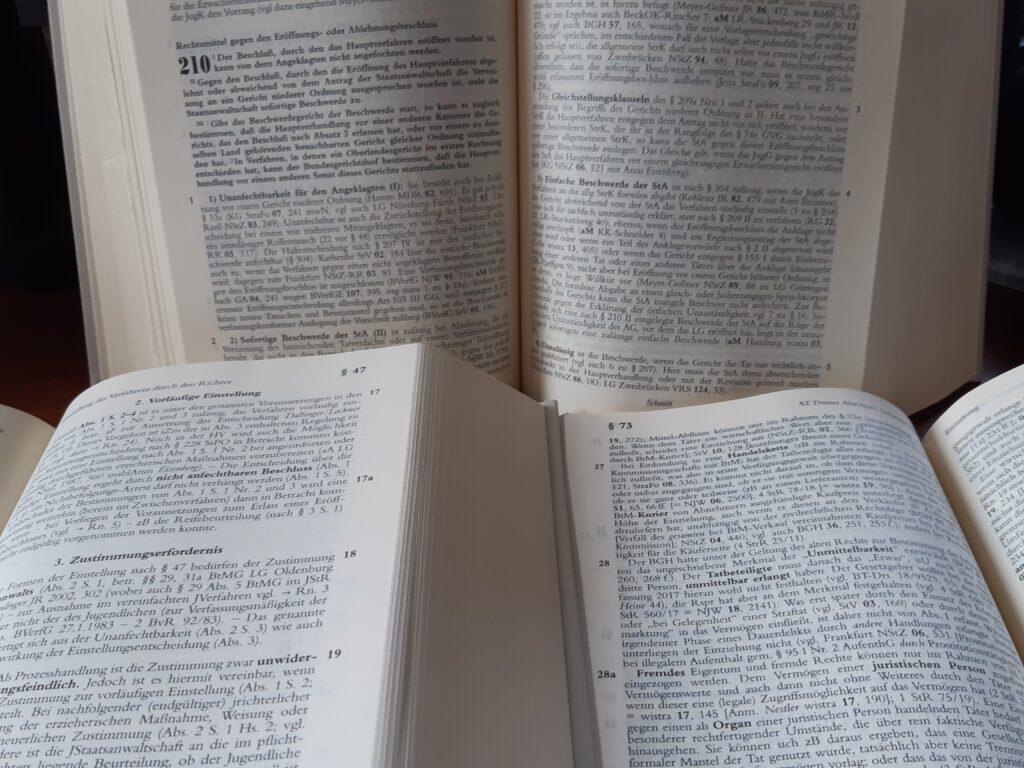

Chinese criminal law scholars have increasingly been establishing links with colleagues in other jurisdictions and drawing benefits from comparative research, and more than anything else with those from Germany. As both Germany and China are at their core civil law systems, and German scholarship in criminal law historically had, and still has, a reputation abroad for a high degree of doctrinal sophistication that may appeal to other legal systems with a similar conceptual DNA. One major factor which keeps recurring in the recent Chinese debate is the dramatically increasing level of interest in a particularly Teutonic tool of legal scholarship, the code commentary.

China is currently carefully reconsidering its previous stance with regard to substantive criminal law, in that reliance on the old Soviet-based criminal code is gradually being replaced by a concept that is owned by Chinese legal scholars, practitioners and law-makers, and shaped to the indigenous principles influencing and guiding modern Chinese culture and society. In other words, Chinese criminal law is increasingly progressing to a Sino-centric understanding of law based on the founding principles of the People’s Republic, the current policies of the CPC and the more recent wider guidance by Xi Jinping Thought as expressed for example in the two volumes of collections of President Xi Jinping’s ideas, The Governance of China.

Addressing the need to ground any law reform on the prevailing conditions in China and the need to lay the “emphasis on what is practical, what is contemporary and what is quintessentially Chinese”, Xi Jinping expressly realises the benefits and risks of international and comparative engagement in the context of law reform:

“Basing our work on reality does not mean that we can develop the rule of law in isolation from the rest of the world. The rule of law is one of the most important accomplishments of human civilization. Its quintessence and gist have universal significance for the national and social governance of all countries. Therefore, we must learn from the achievements of other countries. However, learning from others does not equate to simply copying them. Putting our own needs first, we must carefully discern between the good and the bad and adopt the practices of others within reason. Under no circumstances can we engage in “all-out Westernization”, or a “complete transplant” of the systems of others, or copy from other countries indiscriminately.”

Using a “Western” tool does not eo ipso equate to crafting Western things with it, in other words: process does not equal substance. From the point of view of a Chinese domestic debate about the pros and cons of commentary use it is ultimately irrelevant whether Western lawyers approve or disapprove of the material and political essence of the legal system which the commentary is meant to elucidate. Elucidation is a worthwhile and unobjectionable aim in and of itself and, as the inevitably patchy practice of the SPC in issuing interpretative guidelines has shown, something for which the need is clearly felt at the highest echelons of the Chinese legal establishment.

The choice of analytical or conceptual lenses is paramount for the contribution a commentary can make to the development of any area of law, but certainly in the field of criminal law. This process of choice begins, however, even with the meta-question of who decides these analytical parameters: Will they be ordained by the Party structures or the SPC or will each academic (team) be free to choose their own? In the former case, it is to be expected that a much wider array of society- or community-related criteria will find entry into the project and serve as a more or less tight strait-jacket for the development. Even if the overall tendency might be to move away from the old Soviet-style model, it is unlikely that a major shift towards an ideology incompatible with modern Sino-socialist thinking would be advocated or tolerated.

It might be highly beneficial for the Chinese context to rethink the relationship between academia and practice. Judicial and wider practitioner involvement in commentary writing would appear to be crucial in order to achieve a harmonious blend of scholarly penetration of the material on an analytical basis with the views and practical experience of seasoned – and ideally also scholarly-minded – judges, prosecutors and counsel.

Finally, what shape should Chinese commentaries adopt? The easy avenue of copying the mere phenotype of the various German commentaries may make it difficult, if not to say unattractive, for the Chinese debate to reflect on its own approach from scratch, as it were. One might be tempted to say that the desire for a working commentary culture and the apparent respect for the German experience may have forestalled a proper fundamental debate within the Chinese legal community about the merits and aims of engaging in commentary writing, its underlying philosophical parameters and policy directions – in other words: Is there a particularly Chinese DNA that would give rise to a different genotype?

While the focus of this paper is on exploring the lessons that can be drawn from the German case, it is far from clear that this model is best-suited for the Chinese legal environment, possibly adding the further qualifier: At this time? The current relationship between academia and practice and the alleged lack of practitioner interest in scholarly exploration may militate in favour of a less ambitious format, at least initially: Judicial practice may be unlikely or unwilling to have recourse, leave alone contribute to commentaries if their impetus is too much focused on the academic debates of scholars and does not sufficiently address the needs of practitioners.

Overall, the situation appears rather more complex than it might seem at first glance. There are two Chinese proverbs, “Be not afraid of being slow, be afraid of standing still” (不怕慢, 就怕停), and “Teachers open the doors, you enter by yourself” (师父领进门,修行在个). In the debate about the proper use of the idea of commentaries in China, it seems that these proverbs may prove to be wise counsel.

Michael Bohlander’s paper, published with Peking University Law Journal, is now available here.

Professor Michael Bohlander holds high judicial office as the International Co-Investigating Judge in the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia, having been on leave from Durham University and serving as a full-time judge at the Court in Phnom Penh from 2015 – 2019, and again since April 2020 after his re-instatement in the post by the United Nations Secretary-General, to deal with residual litigation. He is also on the roster of international judges at the Kosovo Specialist Chambers in The Hague, to which he was appointed in February 2017. His extensive published research on German, English, comparative and international criminal law has found wide reception, including outside academia. In his book series, Studies in International and Comparative Criminal Law with Hart, Liling Yue recently published Principles of Chinese Criminal Procedure.