A think piece by Michael Liu

More than one year ago, China’s former Ambassador to the Netherlands, Dr. Xu Hong (徐宏) passed away in Beijing at the age of 57. Xu was diagnosed with a malicious cancer a year before and returned to China for treatment shortly after. Xu is a well-known figure among China’s international lawyers. Given the rather late stage of the illness, his death came as less of a surprise than the diagnosis itself. Yet immediately, social media was flooded with memorial notes and tributes to him. The amount of regret for his departure went beyond the common respect for a senior authoritative figure. He was in a high and powerful position (位高权重), but what struck me most was his unusual sincerity.

While saddened by abruptly losing a well-respected figure, I am also intrigued by the question why he is held with such high esteem by China’s international lawyers. Why is he so much missed, and what makes him different? To answer these questions, I interviewed a dozen people in the circle of international law who knew him. Some of them were his colleagues, superiors and subordinates, or “comrades” in the bureaucratic system, some were opponents who didn’t share his views, some were ordinary friends, or just people who had observed him closely, some inside China and its information great firewall (防火墙) and some outside.

Who is Xu?

Xu is better known to China’s international lawyers as Director Xu or Xu Si (徐司) than Ambassador Xu. Prior to the post of Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary to the Kingdom of the Netherlands, Xu served Director-General of the Department of Treaty and Law of the PRC’s Foreign Ministry (外交部条法司) from 2013 to 2019, which is the top authority on matters of international law in China[1].

For what we know, he is a career diplomat. The Foreign Ministry was his first job upon graduating from Wuhan University in 1985 and only employer in his short-lived life. Xu held several different positions, regularly rotating back to his base, the Department of Treaty and Law, each time on a higher rank. With some pride, he described it as a place with overcrowded and rustic offices, but many important figures in international law when he first joined: “When seeing these senior figurers, I am immensely in awe and felt I am in a sacred palace.” [2]

The State and its lawyers

For a long time, Chinese authorities have been ambivalent and anxious about lawyers’ role in state affairs. Legal professionals are perceived to be influenced by liberalism .[3] Occasionally, the state orchestrated campaigns against “hard core litigant lawyers”(死磕律师). Those who invoke international rules for their cause are also unwelcomed with situations sometimes escalating to a diplomatic crisis for the State.[4]

While the “sticks” in the hands of Chinese authorities have been better studied, recent research also shed light on the “carrots” side of the mission to create a rank of state-adjacent lawyers. Stern and Liu (2019) found that the state uses different channels to celebrate “the good lawyer”, those who are willing to work closely with the authorities and urge critical colleagues to separate private beliefs from public behavior. Essentially, by curating an appealing state strand of legal professionalism rather than relying on coercion alone, lawyers can participate in politics without opposing the regime.[5] Answering Stern and Liu’s call to examine this further with “varieties of legal professionalism” and different segments of the Chinese bar, this essay looks into how among China’s international lawyers an authoritative figure is established.

To help understand the context, I will use Matthew Erie’s (2021) framing on the exchange between the Party-State and Chinese legal academia, “a relationship that lies at the heart of understanding why and how Chinese scholarship on international law assumes the forms it does”:

“Party-State and international law scholars mutually assist each other for their own benefit. The former obtains expert commentary which is aligned with its political and geostrategic aims. The latter earns access to data and government funding, a phenomenon which I will now turn to”.

For example, in a well observed event among Chinese international lawyers, Xi Jinping made a high-profile visit to the China University of Political Science and Law (CUPL) on its sixty-fifth anniversary in 2017. He met with senior legal academics from different universities and made a speech during which he exhorted the students to contribute to building “global rule of law” (世界法治). Reciprocally, Professor Huang Jin, President of CUPL, has proposed that international law be elevated to a “first-level academic discipline” (一级学科) in China, effectively calling for a greater standing of international law scholars in Chinese academia. Professor Huang is also an advocate of applying Xi Jinping Thought to international law. The message that emerged from this exchange is that the Party-State and international law scholars mutually assist each other for their own benefit: The former obtains expert commentary which is aligned with its political and geostrategic aims. The latter earns access to data and government funding.

My interviews confirm that Xu played an important role in both processes: the government’s encouragement for international law academics to strategically use research funding, study areas of international economic law and the law of the sea to best protect China’s interest, as well as enabling access to data for researchers. For instance, Xu’s Department of Treaty and Law has continuously recruited mid-level international law academics to join the rank with temporary affiliations. Institution-wise, the same Department also established a Consultative Committee on International Law during Xu’s tenure, consisting of mostly academic experts.[7]

These efforts pay off. When Chinese legal academics who specialize in the study of international law have rallied to Beijing’s cause when faced with adverse arbitral award in the South China Sea Arbitration Case. In Ku’s (2016) account,

State broadcaster China Central Television America recently reported that “300 Chinese legal experts” reached a “unanimous” opinion that “China should abstain from participating in the case, because the arbitration panel has no jurisdiction over the dispute [and] China has legitimate rights under international law to reject the arbitration.” State news agency Xinhua noted that the China Law Society, an organization which represents all academic lawyers in China, released a similarly unanimous and supportive statement of China’s legal position. Xinhua also recently touted an open letter endorsing China’s legal position signed by hundreds of young Chinese international law scholars studying overseas. And leading Chinese scholars have written essays defending the government’s position.[8]

A year later, the Chinese Journal of International Law, an Oxford University Press journal headed by Professor Yee, a member of Xu’s Consultative Committee on International Law, published an extraordinary 500 page “Critical Study” of the arbitral award by the Chinese Society of International Law (CSIL). The study was hailed as unbalanced,[9] and the Working Report of the Board of Chinese Society of International Law (2013-18) openly reported that it was carried out “under the supervision and leadership of the Foreign Ministry”.[10]

Ku finds that scholars within the Chinese legal establishment have indeed either expressed support for Beijing’s position or have kept silent. Reasons, he argues, are censorship, retribution, and nationalism. My interviews also show in addition to material encouragement and disencouragement, Xu’s personal charisma or mianzi (面子) might have contributed to the standing of Chinese legal establishment in this case.

Schachter described international lawyers as a professional community which, though dispersed throughout the world and engaged in diverse occupations, constitute a kind of invisible college dedicated to a common intellectual enterprise.[11] It seems while China is eager to bolster its standing in this “invisible college”, it is also raising its very own national not so invisible college. Xu is the central figure of these two parallel efforts.

How did Xu win the respect of China’s international lawyers?

Many interviewees told me that the situation should be de-romanticized before this question can be answered, especially in the Chinese society which emphasizes relationships. There are a lot of pragmatic and realistic aspects behind Xu’s high esteem. All of the interviewees seemed to have their own understanding of this point. A professor with a great deal of practical experience succinctly summed up what he had observed:

First of all, I don’t know him well, but as far as I know, he has a very good reputation in the academic community, and it’s normal for people to think well of him; Second, he is the Director of the Department of Treaty and Law of MFA, and for Chinese international law scholars, he is the biggest owner and distributor of resources, and everyone must say good things about him; third, he is from Wuhan University, and the Chinese international law circle, in a sense, is the alumni circle of Wuhan University.

This was also indirectly confirmed by a former colleague. When I asked him to explain the extraordinarily high number of tributes on WeChat, this former colleague said that Xu was well-connected and had long-standing connections to many because he held this pivotal position for a long period of time. His sudden death shocked many.

But what seems natural to this former colleague may have another dimension. Among Chinese officials, being able to put down their “officialism” and communicate with ordinary people is unusual, especially against the background of the almost insurmountable barriers between those inside and those outside the official system 体制内外. Few pivotal officials are accessible. In contrast, as almost all interviewees stated, Xu was a very humane and good person, had no airs, and was always helping others. This reminds me of how retired Chinese president Jiang Zeming is being affectionally remembered in China. One young interviewee added that Xu drew a strict line between personal time and work time. This made people around him think that he was a humane person (“of flesh-and-blood” 有血有肉的人). Many mentioned that Xu cared about his subordinates and colleagues, respected young people and gave them chances to grow.

His willingness to help others despite his high position surprised people who came into contact with him for the first time. A recent graduate recalled that when she sought advice from him, “not only did he immediately reply to my message, he also immediately introduced me to his colleagues and asked them to follow up. I was dumbfounded at that time. I have never seen such a good person”. A professor who worked briefly with him and his colleagues said that “working with them gave you the feeling that they were there to serve, not to command.”

Another character that sets Xu apart from others is that he is portrayed differently than his diplomatic peers. As many Chinese diplomats as well as the MFA’s spokesperson adopted aggressive language and dogmatism and were therefore dubbed “wolf diplomats”, Xu remained comparably moderate. One interviewed researcher, who is known for his critical stance towards the Chinese government, observed that Xu “speaks with reason, unlike other ambassadors.” In his opinion, Xu’s handling of the South China Sea arbitration shows that although while he must stick to the official political line, he makes efforts to support his position with legal language. The same is true of the document issued later under his leadership regarding the Sino-British Communique concerning Hong Kong. Chinese and foreign observers note that they understand his position and respect his effort to represent it.

It is a sign of Xu’s professionalism that people with different positions appreciate him. But, with the exception of one former colleague, to those who have worked with him, the most memorable traits are is humane attitude and willingness to help others.

Epilogue: Xu in my own eye

Xu and I are members of the same community, but although working on the different front lines of international law, I only had one direct contact with Xu and caught a glimpse of his personality.

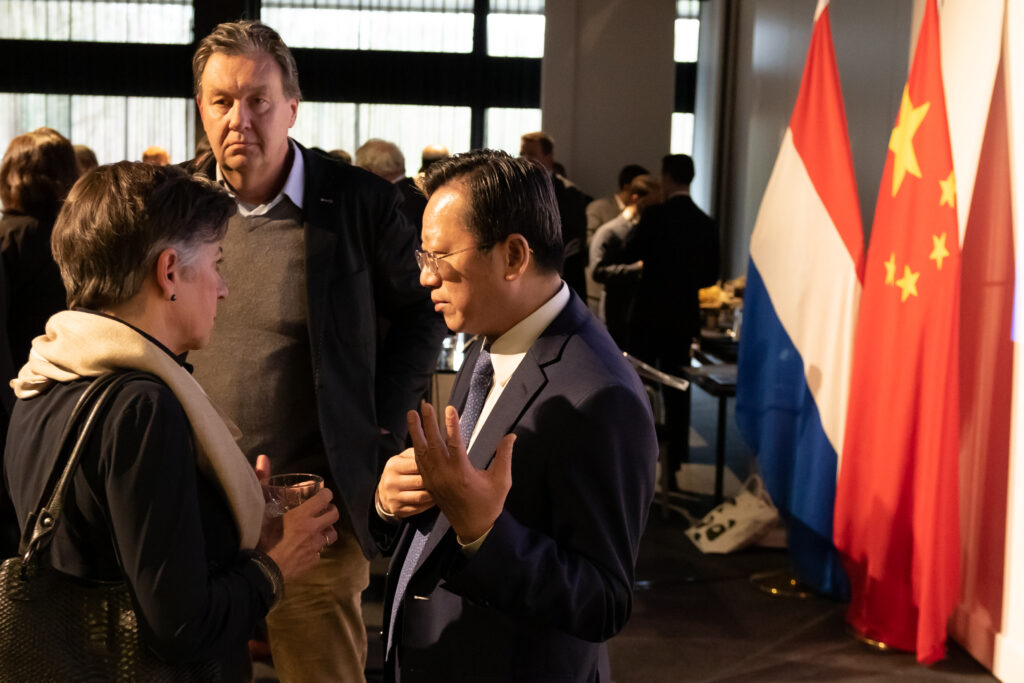

In the summer of 2019, I organized the ICC Chinese Moot Court Competition and took around 100 Chinese students and teachers to the Netherlands. Through a friend, I was able to arrange a visit to the Chinese Embassy for our group. It was nice to see the students cheerfully taking photos with Ambassador Xu. Although Chinese embassies often proclaim to be “the home to the overseas Chinese nationals”, those of us who needed to work with them from time to time certainly don’t feel that way. This time, not only did Xu come out himself, he also thoughtfully arranged for the young diplomats in the embassy to come out and meet with students.

On the same day, I spoke to Xu for the first time. Xu knew about the moot court competition before as parts of his team would participate as judges. I expressed my gratitude to him as the organizer of the competition. I will always remember his response. After a brief exchange on the particulars of the competition, he told me that he was concerned that recently the Philippines had been trying to use the court to stir up attention, and asked whether I had noticed. Initially, I did not understand what this had to do with our moot court or my engagement with the Court. Later, I realized that he used our informal channel, the non-governmental organization I represented, to convey his government’s “concern” on Philippines’ move. I then understood better the diplomatic term “concern” and how it works in a multilateral setting with different stakeholders involved. The impression I gathered is Xu might be a sophisticated diplomat who thinks about work all the time.

I am glad I got it half right and half wrong, and I deeply regret that was my only lesson from him in this invisible college.

Michael Liu is a lawyer and civil society activist from China. The NGO that he founded in 2012, “Chinese Initiative on International Law” (CIIL) has been actively engaged in rule of law training, refugee relief and gay rights advocacy in and out of China. The organization has also been granted a consultative status with the United Nations (ECOSOC). Previously, Michael was a victims’ counsel at the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (Khmer Rouge Tribunal) and worked at the International Criminal Court, the International Committee of Red Cross and a private law firm (Fangda Partners) under various capacities. His PhD project at Leiden University is about the rise of China as a norm shaping force in the global human rights discourse

[1] In addition to the Department of Treaty and Law, the Department of Boundary and Ocean Affairs (边海司) and the Department of International Organizations and Conferences (国际司) also deal with issues of international law.

[2] Interview with Xu Hong at the 40th anniversary of international law institute of Wuhan University (武大国际法所四十周年所庆之“校友风云榜”,徐宏大使访谈录:漫漫外交路 拳拳珞珈情) https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/aXs0OiuGUoIQ3aXoZyAFWg accessed 24 March 2022.

[3] See Eva Pils (2018) Human Rights in China: A Social Practice in the Shadows of Authoritarianism, Wiley; Di Wang and Sida Liu (2020) Performing Artivism: Feminists, Lawyers, and Online Legal Mobilization in China’, Law and Social Inquiry 45(3), pp. 678 – 705 678.

[4] Yaxue Cao (2014) The Life and Death of Cao Shunli (1961 — 2014), China Change, 18 March 2014, https://chinachange.org/2014/03/18/the-life-and-death-of-cao-shunli-1961-2014/, accessed 1 April 2022.

[5] Rachel E Stern and Lawrence J Liu (2020) The Good Lawyer: State-Led Professional Socialization in Contemporary China, Law and Social Inquiry 45(1), pp. 226 – 248.

[7] The Editors (2021) In Memoriam: XU Hong (1963-2021), Chinese Journal of International Law 20(1), 217.

[8] Julian G Ku (2016) China’s Legal Scholars Are Less Credible After South China Sea Ruling, Foreign Policy, 14 July 2016, https://foreignpolicy.com/2016/07/14/south-china-sea-lawyers-unclos-beijing-legal-tribunal/, accessed 24 March 2022.

[9] Douglas Guilfoyle (2018) A New Twist in the South China Sea Arbitration: The Chinese Society of International Law’s Critical Study, EJIL: Talk!, 25 May 2018, https://www.ejiltalk.org/a-new-twist-in-the-south-china-sea-arbitration-the-chinese-society-of-international-laws-critical-study/, accessed 24 March 2022.

[10] Work Report by CSIL(中国国际法学会理事会工作报告) on May 22, 2018 https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/Xv8Kij_bDuqMETULvUfMqg

[11] Swethaa S Ballakrishnen and Sara Dezalay (eds.) (2020) Invisible Institutionalisms: Collective Reflections on the Shadows of Legal Globalisation, Hart Publishing, an imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing.