A paper by Leigha Crout

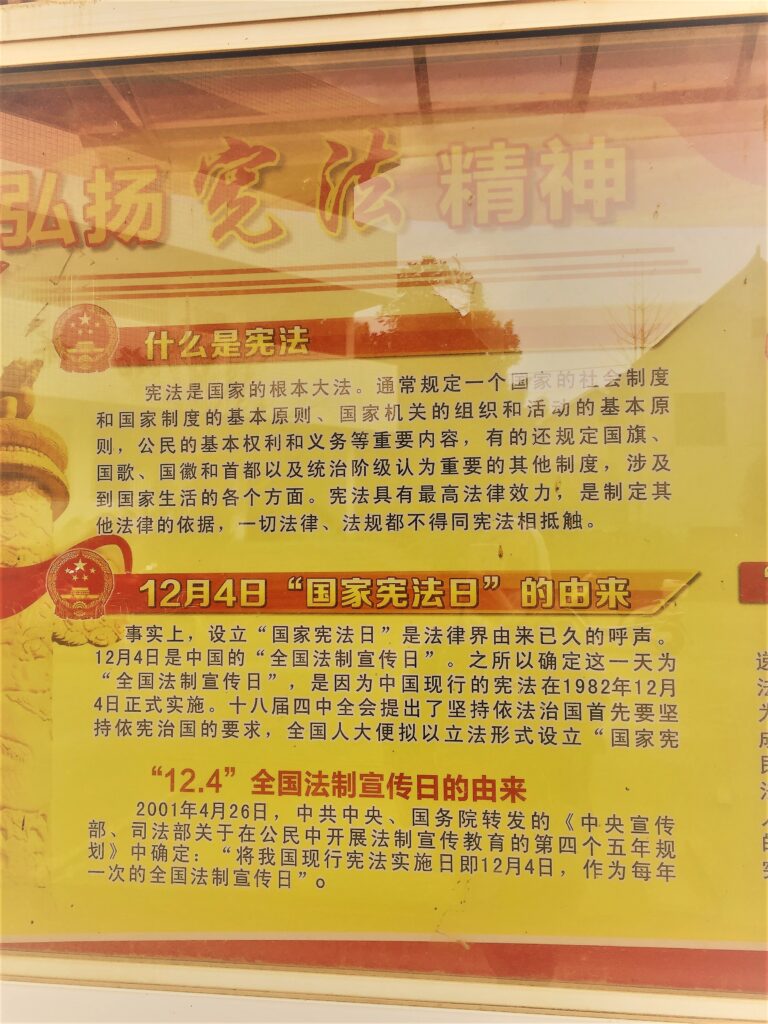

The Constitution in the People’s Republic of China (the PRC or China) has experienced a modern revival under the Xi administration. Both the Communist Party of China (the CCP or the Party) and state leaders have called upon the nation to rely upon the guiding force of the Constitution and its laws in recent years and to adopt Xi Jinping Thought on the Rule of Law (习近平法治思想) in enforcing legal mandates. However, it is also clear that this new emphasis on constitutional law – and by extension, constitutionalism – excludes some of the ideas traditionally associated with a constitutionalist state.

Core facets of constitutionalism, including judicial independence and the separation of powers, are notably absent in its new and contextualised version in China. This is best represented in the adoption of the 2018 Constitutional amendments, which eliminated term limits for the state’s highest offices (one of few procedural limitations consistently enforced by China’s leadership), equated the ‘leadership of the Communist Party of China’ with the founding ideology of the nation, and further blurred the boundaries between Party and state governance. Now, it seems China’s leadership has embraced a political-style constitutionalism that relies on the leadership of the Party as the real or ‘living constitution’ of the nation.

Adopting a historical perspective, this paper analyses the development and progressive implementation of China’s four constitutions, using three interrelated frames – ideology, text, and judicial implementation – as a metric for determining how the theoretical footholds of this new ‘constitutionalism’ within China developed over time.

This work begins with an overview of the competing legal philosophies that influenced dynastic China and preceded the development of the state’s first constitution. Two polarised conceptions of law predominated – Confucianism, which emphasizes social rules and the maintenance of harmony, and Legalism, an ideology that presupposes humankind to be cruel and generally unlawful. Whereas Confucianism would eschew formal institutions for the resolution of conflict as disruptive to social order, Legalists preferred a strong administration, detailed edicts and harsh penalties for violations of the law. Both philosophies, though seemingly contrary, continue to exert great influence on governance in modern China; for example, Xi Jinping is well known to cite the Confucian classics in his speeches, while encouraging the development of a ‘legalistic’ administration.

The form and content of most of these documents traced the historical political trajectory of the state. The 1954 Constitution, for instance, was a product of the Communist Party’s victory in the Chinese civil war and the nation’s then-strong alliance with the USSR. The text supported the supremacy of the vanguard party and included a stronger program for collective entitlements and responsibilities of citizens. In terms of judicial enforcement, this text was explicitly excluded from the courtroom in a communication from the nation’s highest court (the Supreme People’s Court) to a lower court, in confirming that the Constitution could not be cited in criminal matters.

The short-lived 1975 Constitution reflected a turn within the Mao Zedong era – the Cultural Revolution, a national movement which endeavoured to ‘cleanse’ the nation of its traditionalist past and Western influence to form a new Communist revolution for its people. Alongside many of the nation’s historical relics, the legal system was fundamentally hollowed out during this time as lawyers and judges were detained, disappeared and sent to labour camps or re-education facilities. Judges held court on limited matters, primarily on divorces or important criminal cases. In many ways, China is still recovering from this generational loss of its legal profession. In its text, the Constitution reserved absolute authority for the CCP. While different branches of the government were maintained, all were required to express deference to the Party. Rights were also condensed to merely four articles, leaving little room for enforcement. Fundamentally, the 1975 Constitution represented a legitimation of the power already subsumed by the Communist Party and proved to be an unsustainable model that was reformed upon Mao’s descent from power.

The 1978 Constitution was also transitional – taking the state out of the Cultural Revolution and paving a path for the modern era. This text was an amalgamation of elements originating from the 1954 draft and its immediate predecessor; it once more expanded the number of constitutional rights, while also maintaining the structure of deference to the Party. Ultimately, reformists within the state resistance were successful in calling for a new text in 1982 that reflected the contemporary era of constitution building and economic globalisation. This current Constitution in many ways mirrors the common programs of democratic nations. It includes traditional principles of a constitutionalist state, like judicial independence and provisions for the separation of powers. It also adopts a robust commitment to rights, improved by the 2004 amendments’ addition of an explicit state obligation to respect human rights.

Since its adoption, the Constitution has been amended five times, and most subsequent modifications brought China closer to constitutionalism in its organic sense. In 2001, the Constitution was judicialized for the first time when the nation’s highest court relied on the text to vindicate a plaintiff’s constitutional right to education (though this ruling was later vacated).

However, the 2018 amendments brought the state’s Constitution reformation period to an abrupt halt, introducing a ‘New Era’ of constitutionalism with old roots. As a result, this historical perspective is particularly relevant and instructive in today’s China. Human rights and traditional constitutionalist principles within China’s Constitutional text now seem to rival the revived citizen obligations and commitment to Party leadership of the Mao period. These developments are not incidental but represent an intentional reversion to specific historical mandates.

With precepts found in the dynastic and Communist states, this constitutionalism appeals to several key elements of China’s constitutional past. Intentional efforts from the Party to create law ‘suitable for China’ tend to focus on constitutional language from the Mao era, which laid precedent in situating the Party at the helm of the Constitution. Constitutional concepts such as Mao’s People’s Democratic Dictatorship, or the idea that China is a democracy for its friends and a dictatorship for its enemies, have generated fresh debates within state media and domestic literature. Moreover, the state’s efforts towards administrative centralization have echoed within China’s legalist traditions. Taken together, it is clear that the PRC’s legal history plays a newly significant role in the present.

While China’s constitutional future remains unclear, the modern revival of these elements and others signifies a departure from its era of reform. However, many protest a return to the past. While suppression of dissent has become commonplace, activists nevertheless persist in advocating to vitalize their constitutional rights. As resistance efforts continue, it may be that this New Era of constitutionalism has the same transitional nature as its predecessors.

The paper The Evolution of Constitutionalism in the People’s Republic of China: Past and Present was published with the Indiana International and Comparative Law Review. Leigha Cout is a William H. Hastie Fellow at the University of Wisconsin Law School, a PhD Candidate in Law at King’s College London and a Research Associate with the China, Law and Development Research Project at Oxford University. Her current research focuses on constitutional law and change in the People’s Republic of China.