A new paper by Teemu Ruskola

Life is complicated. Theory is simple: democracy is good and authoritarianism is bad. What is more, democracy in a robust sense requires a foundation based on the rule of law. Authoritarian regimes too may have law; however, instead of being constrained by it they rely on it only for instrumental purposes.

These statements seem commonsensical and just like everyone else, I too agree with them. There is a problem, however. It is the strictly binary way in which they are constructed. To stay that democracy is preferable to authoritarianism is not an especially illuminating statement. First of all, neither term is self-defining. To start with, whenever we are talking about modern centralized states, we are always dealing with some kind of representative democracy. However, every form representative democracy entails necessarily some kind of distortion, with some people winning and other people losing. One Senator cannot literally “represent” the views of 20 million people, even if we put aside the problem of legalized corruption known as campaign finance. There is no pure democracy as such—except maybe a direct democracy on the model of the Athenian polis, and even there the people who were the loudest, tallest, and the sweetest talkers—let us call them demagogues—had a disproportionate influence (not to mention the wholesale exclusion of women and slaves).

Second, while democracy is, by definition, superior to authoritarianism, that does not mean that there could not be other worthwhile ways of organizing politics. Democracy, for all its potential, has serious limitations as well. At least in its electoral form, it is not well-equipped to address questions of intergenerational justice (the unborn do not vote), nor to attend to the relationship between humans and their environment (trees have no standing, as Christopher Stone famously said)—the most fundamental relationship of all, as we find ourselves careening toward environmental collapse.

Put differently, democracy is ultimately a historical category, not the transcendental telos of all politics, and it can take dramatically different forms. Accordingly, it can work relatively well or not, depending on historical, social, and political circumstances. In its contemporary manifestations, it is very difficult to separate democracy from the histories of nationalism and capitalism, most notably. When we talk about democracy today, we are usually referring to a political union between some kind of liberal democracy and some form of capitalism—a system where elections function more or less as a giant calculator whose main task is to aggregate individual preferences.

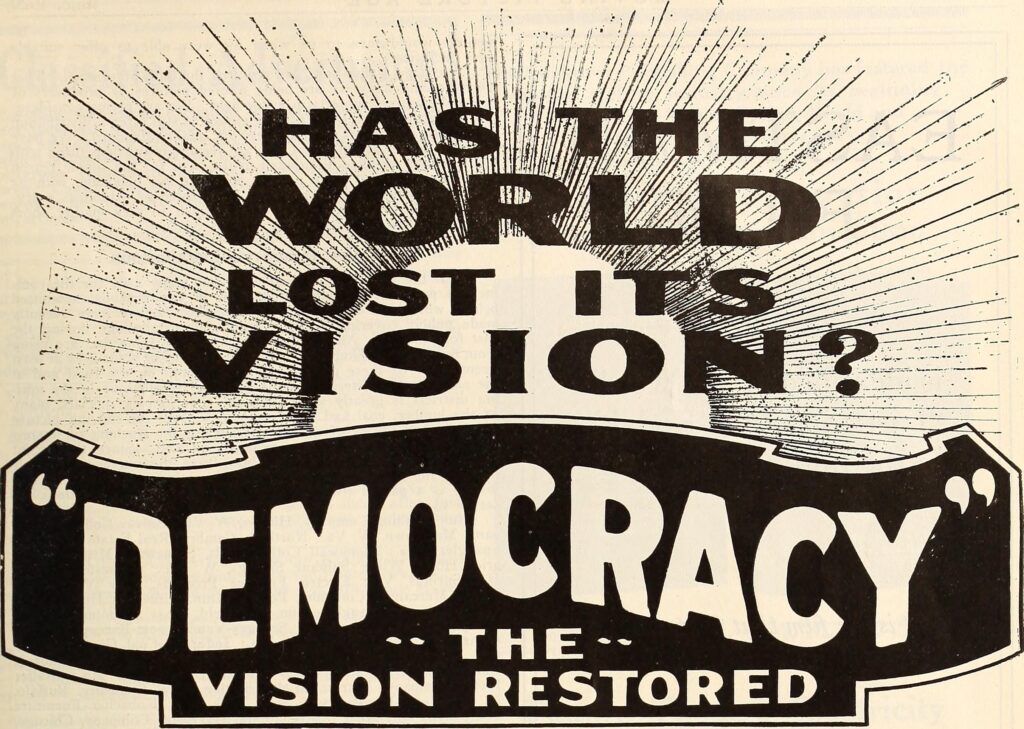

Whatever the virtues and the limits of this brand of democracy may be, what troubles is me that especially after the end of the Cold War this particular understanding of democracy been universalized. It has become essentially a religion, and a rather jealous one: a monotheistic faith that does not recognize any valid alternative. It has become a missionary project that aims at nothing less than the standardization of political forms and political subjectivities on a global scale.

In a recent article, I use Shucheng Wang’s excellent book Law as an Instrument: Sources of Chinese Law for Authoritarian Legality as a point of departure for reconsidering the conventional opposition between liberal and authoritarian forms of legality. I argue that this opposition is in turn embedded in an even more elemental distinction between different state forms. Turning to Montesquieu’s The Spirit of the Laws, I first investigate the historical and geopolitical processes by which modern political theory reduced the political universe into three species of states (republics, monarchies, and despotisms) and then merely two (democratic and authoritarian states). Next, I turn to the contemporary genealogy of the concept of rule of law, which arose first as a critique of the rise of the administrative state in the West and then became a means to delegitimize socialist conceptions of legality. Finally, I conclude by focusing on the People’s Republic of China to evaluate the utility of assessing its legal order in terms of authoritarian legality as well as in terms of democracy more generally.

We should most certainly continue to improve existing democratic institutions, but we should not allow ourselves to be completely dazzled by democracy, whether as a political idea or a political practice. It must not foreclose our ability to imagine other kinds of politics and other kinds of institutions. A constitutional democracy is one way of coordinating life among humans, but it cannot be the only, or final, form of politics, especially in an age where our most urgent and intractable problems are global. Insofar as we are looking for non-liberal forms of justice and politics, maybe—just maybe—the historical experience of China can help us imagine alternatives, especially as the limits of electoral democracy are being tested today all around the world.

Teemu Ruskola is Professor of Law & Professor of East Asian Languages and Civilisations at the University Pennsylvania. He is an interdisciplinary legal scholar whose work addresses questions of legal history and theory from multiple perspectives, comparative as well as international, frequently with China as a vantage point. Ruskola is the author of Legal Orientalism: China, the United States, and Modern Law (Harvard University Press, 2013), co-author of Schlesinger’s Comparative Law (Foundation Press, 2009), and author of numerous contributions to law reviews, from the American Journal of Comparative Law to the Yale Law Journal. He is also co-editor (with David L. Eng and Shuang Shen) of a special double issue of the journal Social Text on “China and the Human.”