Laura Formichella and Enrico Toti interviewed Jerome A. Cohen

Professor Cohen, more than forty years have passed since the book you edited Contemporary Chinese Law: Research Problems and Perspective, it was exactly 1970. The four hundred pages volume contains important contributions on themes concerning Chinese law. Specifically, your paper “Chinese Attitudes Toward International Law – and Our Own” reconstructs the theme and provides significant reflections and synthesis on the topic. From the 1970s to today, how have Chinese attitudes toward International Law changed?

I started to follow China’s approach toward international law just when the Cultural Revolution began. Changes in the theory and practice of international law in China since 1966 have led to an unthinkable development, of which we have only gradually become aware.

Yet the PRC [People’s Republic of China] had demonstrated a revolutionary outlook toward the international community from the time of its establishment in 1949. This was in obvious response to the world community’s rejection of China’s new revolutionary government. If the United States had recognized and established diplomatic relations with the PRC from the outset of the communist regime, we might have moderated its hostility. For our own domestic political reasons, however, we did not. The United States also opposed the PRC‘s entry into the United Nations under any formula. Thus, the United Nations rejected the PRC as the lawful representative of the Chinese people, despite its control of the Mainland and despite the fact that the ROC [Republic of China] authorities had fled from Mainland China to Taiwan. The government of the ROC held onto the Chinese seat in both the Security Council and the General Assembly, even though it lost the civil war. Moreover, immediately after the United Nations rejected the PRC, when the United States decided to pursue the retreating North Korean forces into North Korea and possibly eliminate the buffer state on China’s border, the entry of “Chinese People’s Volunteers” into the Korean conflict served to enhance the PRC’s revolutionary rhetoric against the existing world organization. The United Nations, not only the United States, became China’s enemy in Korea.

Even after the Korean Armistice in 1953 and the PRC’s adoption of “the five principles of peaceful coexistence” and a more moderate foreign policy, the UN continued its exclusion of Beijing and Chairman Mao did not abandon the hope of establishing an international organization of developing countries that might rival the United Nations. China’s distrust of the Western-controlled United Nations was matched by its distrust of the international law reflected in UN practice. Moreover, most major Western countries still refused to recognize and establish bilateral diplomatic relations with Beijing. In that era, PRC views of international law were shaped by the Soviet Union’s experts, just as China’s domestic legal developments followed the Soviet legal model until the Sino-Soviet split of the late 1950s and the radicalization of the

PRC’s domestic legal system.

The most distinctive of the theories of international law imported from the Soviet Union stated that there were really three types of international law. There was the bourgeois view of international law, to regulate relations among bourgeois states, there was the international law to govern relations between the socialist world and the bourgeois world, and then, there was socialist international law, to govern relations among the socialist states.

Certainly, China’s leaders had good reasons to be cynical about American assertions of international law. During the PRC’s first decade, the United States took many illegitimate, covert actions against China in an effort to undermine the new regime. For example, it flew non-communist Chinese and American CIA agents into China to help organize unrest. Also, after training expatriate Tibetans in mountain warfare in Colorado, it dropped them back into their homeland to stoke the fires of resistance.

In mid-1957, China entered a more radical phase at home and abroad, one that culminated in the chaos of the Cultural Revolution’s earliest years, 1966 to 1969, and resulted in the alienation of virtually every significant country in the world. In that period, China’s practice of international law reached its nadir, especially with respect to violating the rights of foreigners and foreign diplomats in China.

Fortunately, such institutional and ideological non-conformity began to ebb with the end of the most violent portion of the Cultural Revolution in the autumn of 1969, when Beijing began a renewed effort to enter the UN and to complete its normalization of bilateral relations with the major powers. Yet despite Canada’s groundbreaking establishment of diplomatic relations with Beijing in 1970 and the PRC’s UN entry the following year, China’s leaders, still in the midst of fierce internal political struggles in the waning years of Chairman Mao’s rule, revealed a continuing mistrust of UN institutions and commonly understood international law.

A personal anecdote illustrates this point. On June 16, 1972, I had the good fortune to have dinner with Premier Zhou Enlai. I sat on his left and John Fairbank, the great historian of China, sat on his right.

We were both from Harvard and had been members of a Harvard-MIT faculty group of China specialists who, immediately after Richard Nixon’s 1968 election, had given the President-elect and his new assistant, our erstwhile colleague Henry Kissinger, a memorandum proposing steps towards a new American policy toward China. Since the first half of this session seemed to go well while reviewing Sino-American relations and the Vietnam war, I decided to ask about the Chinese Government’s current attitude toward international law. I introduced the topic by suggesting that the PRC, having just become a prominent participant in the UN with a permanent, veto-wielding seat in the Security Council, should also consider sending an expert to serve as a judge on the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in the Hague. That provoked the loud laughter of all the Chinese officials, who plainly thought it a ludicrous proposal. Why, they wondered, should the PRC want to assume a seat on the fifteen-member ICJ, where they were sure most judges would be prejudiced against an Asian, Communist state and would disagree with its views? Moreover, as has subsequently become even clearer, the PRC has traditionally mistrusted settling international disputes through adjudication, arbitration and other forms of third-party decision-making. Despite China’s millennial practice of mediating domestic disputes, even mediation’s more limited third-party participation in international dispute resolution has been shunned by Beijing. I held my ground, arguing that, for permanent members of the Security Council, an ICJ judgeship is one of the perquisites of being a world power and that the PRC should not pass up the opportunity. It took more than another decade before Beijing finally posted to the ICJ the first of what has become a succession of very well-qualified Chinese judges. However, the process of PRC participation in international adjudication is not complete. Like the United States, China has not accepted the compulsory jurisdiction of the ICJ, nor has it accepted participation in the relatively new International Criminal Court, although it has placed capable representatives on certain ad hoc international criminal tribunals.

Moreover, Beijing generally insisted that countries that wished to establish diplomatic relations with it had to acknowledge, to varying extents, that Taiwan should be deemed to be part of China. The PRC’s October 1971 replacement of Taiwan in the UN was the dramatic moment, of course, and would not have been possible if Beijing had not assured all and sundry, at least implicitly, that it would henceforth observe universal standards of international law and practice. Beijing wanted to finally get inside the big tent, and to do so it had to indicate that it would play by the rules.

Other countries had decided that the only way to get China to play by the rules was to finally admit it into the big tent. Thus, the PRC began the process of moderating its statements and its practices relating to international law, and trying not only to become a participant in, but also a shaper of, international law in various forums.

The book that Hungdah Chiu and I did, “People’s China and International Law”, reviews the earliest years of this crucial history. To be sure, a big country with the PRC’s radical tradition could not fundamentally change direction in a day, and, as the following story suggests, the difficulties encountered in the process should not be underestimated.

Finally, at least until the mid-1970s, the impact of the Cultural Revolution on China’s educational, research and bureaucratic systems had left many PRC diplomats and officials ill-equipped to cope with the legal demands of the new situation. I remember another personal anecdote: in 1973, the PRC’s permanent representative to the UN, the very able Ambassador Huang Hua, told me how embarrassing it was that, for lack of a qualified official to fill Beijing’s seat on the UN General Assembly’s Sixth Committee, which is responsible for legal affairs, he had to ask his wife, who was only trained in economics, to do so!

Almost fifty years later, the situation is very different. The PRC has developed impressive expertise in the field of public international law. Its law schools and political science departments offer detailed instruction in the subject by well-trained specialists, many of whom have done advanced study in the world’s leading academic institutions and some of whom have been invited to teach there. These scholars and their colleagues at the country’s many research and policy organizations often publish sophisticated analyses in books, academic journals and media essays, not only in the Chinese language but also in English and other foreign languages, and are active participants in non-governmental international law conferences and dialogues. In addition, they frequently provide advice to various departments of the Chinese government.

Contemporary PRC officials and diplomats are products of this educational system and have developed their legal expertise in sundry areas of international responsibility. This is apparent from their activities while representing their government in many international fora as well as while posted at home to the Law and Treaty Division and other bureaus of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs as well as other agencies within the government, including those that deal with foreign economic and business issues. Some also have honed their credentials while employees of the UN or other public and private international organizations.

Together, this impressive and increasingly large group of specialists brings to bear an important body of international legal knowledge and a potential for acting as a restraining influence upon the exercise of untrammeled official power. Of course, as in the United States and other countries, these experts in and out of government often disagree among themselves about the proper application of international law to inevitably complex and controversial problems, and in any event their views are often overridden by more powerful official decisionmakers who may not be attuned to international legal considerations or who give greater weight to political, military, economic and other factors.

Because of the PRC’s unusually repressive domestic political climate during the Xi Jinping years, to an unquantifiable extent the opportunities for Chinese international law experts to influence government policies and actions are undoubtedly not as great as those enjoyed by counterparts in foreign democracies. Certainly, discretion is the better part of valor when Chinese experts state their views in public. To be sure, there is greater scope for expression when advocating a future course than when criticizing decisions already taken. Yet, Chinese colleagues tell me that today, whether as official or consultant, one has to tread especially carefully when offering opinions, even within the confidential confines of government discussions prior to the making of decisions.

Professor Cohen, a second question on an equally important topic which is key to understanding many other themes. How is the World Trade Organization, as an international forum that seeks to provide a single platform for member states to negotiate bilaterally and multilaterally and aims to foster the spirit of a new international legal and economic order, understood and utilized in China?

Those looking for evidence to encourage the belief that the PRC will increasingly comply with the current rules-based international order usually take heart from its participation in the World Trade Organization (WTO). That participation was preceded by both a long period of intense negotiations concerning the extraordinarily demanding terms imposed upon Beijing’s entry and Beijing’s simultaneous prodigious effort to revamp its laws, regulations, and institutions in order to comply with those evolving terms.

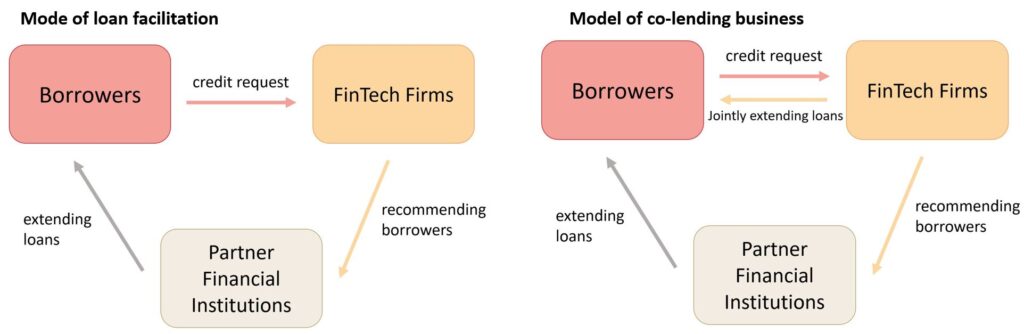

Since its entry in 2001, Beijing has become an accepting and active member of the WTO system, at least with respect to dispute resolution. Those who, because of Beijing’s long-standing aversion to the use of arbitration to settle international disputes between governments, predicted that the PRC would never take part in the WTO’s formal dispute resolution processes have been proved wrong. After a few years of learning the procedures and substance of WTO arbitration, the PRC has become a vibrant participant in the system. It wins some cases and loses others but plays the game! To be sure, the enthusiasm of Chinese spokespersons for the process appears to have diminished a bit of late, and they continue to claim that Western, especially American, experts frequently “outlawyer” them. Yet, ironically, it has been the United States Government under President Trump that has recently posed obstacles to WTO arbitration by opposing the appointment of new appellate arbitrators.

The PRC has also shown signs of warily moving toward participation in the World Bank’s institution for the arbitration of disputes between foreign investors and host governments – the International Center for the Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID). And, of course, Beijing, in addition to its court system, has long supported a vast and complex network of domestic arbitration institutions for dealing with trade, investment and other commercial legal disputes, including those directly and indirectly involving foreign business. The PRC’s recent successful establishment of the multilateral Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), a welcome supplement and possible rival to the World Bank, should also add to Chinese sophistication and support for international dispute resolution. More uncertain and controversial are Beijing’s many ambitious bilateral One Belt, One Road (OBOR) projects, also grouped under the name Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which represent a more obviously self-serving political-economic strategy. The PRC evidently hopes that the BRI will benefit from the services of new Chinese dispute settlement institutions, such as Beijing’s recently-established international commercial courts.

As Susan Finder has written, this appears to be part of an effort to «move the locus of China-related dispute resolution from London and other centers in Europe (or elsewhere) to China, where Chinese parties will encounter a more familiar dispute resolution system». It would be surprising, however, if many of the PRC’s BRI partners with significant bargaining power accept dispute resolution in China instead of in more neutral I, if not their own. Certainly, the PRC, as soon as it established a basic environment for attracting foreign direct investors, insisted that they settle relevant disputes in China rather than in their homeland. Many topics deserve scrutiny, including not only the PRC’s respect for multilateral treaties other than the WTO and UNCLOS agreements, such as those international labor treaties that it has selectively chosen to adopt, but also its adherence to bilateral agreements. The latter topic often receives less attention than the former.

In some cases where bilateral agreements have allegedly been more informally or non-transparently made, it is not possible to confirm either the details of the alleged commitment or the basis for the claim that the PRC has failed to honor it. One example (from outside the area of civil and political rights) is the charge by the United States Government that in 2015 Xi Jinping promised not to militarize contested islands in the South China Sea, yet nevertheless proceeded to quietly do so.

Another is the American charge that, also in 2015, the two governments agreed not to engage in cyberhacking of the other side’s commercial enterprises but that Beijing, after briefly suspending such attacks, subsequently resumed them. In some cases where China has formally committed to bilateral agreements, its implementation has been questionable. An even more recent example of Beijing’s highhandedness In a bilateral consular dispute occurred when in late 2018 it famously detained two Canadian nationals in apparent retaliation for Canada’s cooperation with an American request to extradite a major Chinese business executive. The hapless detainees, seemingly held as hostages more than legitimately suspected criminals, were not given the full protections prescribed in the Sino-Canadian consular agreement.

Although minimal consular access to each of them was belatedly permitted, they both continued to be kept incommunicado and denied access to required legal assistance, ostensibly on the basis of Ministry of State Security suspicion that they represented threats to national security. They were also reportedly subjected to all-night lighting in their detention cells. It is unfortunate that, following their ultimate release from illegitimate detention, these detainees have not responded to calls for them to reveal further details of their suffering.

Since the end of the 19th century, when China began its process of modernization, the Western expression “rule of law”, in Chinese 法制 fǎzhì, has continued to spread among the Chinese and in academic circles. There is now a strong desire for the rule of law to take hold and there remain many expectations.

However, China’s Five-Year Plan for the Construction of the Rule of Law, between 2020-2025, contains a notion that departs from that conceived by the United Nations, the United States, and the European Union, particularly with regard to this Communist regime’s rejection of the separation of powers and the independence of the judiciary and its completely different conception of human rights and democracy. On this issue too, we would like to hear your views. Let us go to the heart of the matter.

The subject is topical and of great interest. I have spoken on numerous occasions on this sensitive issue and have been able to note the difficulty of Chinese scholars to make analyses free from the pressures of the Communist Party. Happily, I was surprised and pleased by the formidable essay of Professor Ruiping Ye, when I was invited by the International Journal of Constitutional Law to comment on her disquisition (our blogpost). She is not based in the PRC but in the law faculty of New Zealand’s Victoria University of Wellington and is therefore literally remote from the conflicting pressures to which Chinese scholars of constitutional law are generally subject. Based on my knowledge, I can attest the accuracy of her characterizations and analysis.

The periodization that the author Imposes upon the post-Cultural Revolution PRC determination to replace Chairman Mao’s cruel chaos with an appropriate legal system seems correct. The 1978-89 era was an age of great, groping, intellectual ferment. There was a broadly shared felt, if inchoate, need to work toward the goal of subjecting “government,” including the Communist Party that controlled the government, to the law that was gradually being enacted and that would embrace concepts such as “equality before the law” and “judicial independence”.

Even after the political fall of the reformer Hu Yaobang as formal Party leader, his successor was also a reformer, the able and dynamic Zhao Ziyang, who continued the vaguely articulated quest to find a way to limit the power of the Party and produce “government under law”. Zhao proposed disentangling the Party from day-to-day state operations, confining it to policy formulation, selection of personnel, and other general matters. If successful, this effort would have developed the rule of law in China.

As Professor Ye recognizes, «Given that China was at the beginning of rebuilding a legal system, fundamental rule of law principles could not be realized overnight, but the blueprint was drawn and the foundation was laid, upon which details could be added and structures could be built».

Sadly, this was not to happen. The military massacre of at least hundreds of peaceful protesters that took place on June 3-4, 1989 near Beijing’s Tiananmen Square ended the possible reform era. Threatened with popular overthrow, the Party’s suddenly revamped leadership, after actually placing the newly-deposed Zhao Ziyang under house arrest for what would be the last sixteen years of his life, promptly abandoned

its flirtation with Westernized “government under law”. In its stead, it chose what may be encapsulated as “law under government”, a path much more congenial to the imperial traditions of the “Central Realm”.

Indeed, there is a marked similarity between the Party-state’s enthusiastic embrace of “rule BY law” and the legalist philosophy of government adopted by China’s first emperor. Over two thousand years ago, his Qin dynasty unified the country through uniform application of laws authorizing unchallengeable harsh punishments.

Ironically, there was during this second post-1978 period, which can be seen as lasting roughly from mid-1989 until the 2012 ascension of Xi Jinping as Party General Secretary, an enormous amount of apparent legal progress. It featured constitutional amendments, legislation on many topics including administrative law and government information disclosure authorizing the right to sue officials in circumscribed circumstances, other procedural and institutional improvements, development of an increasingly sophisticated judiciary and legal profession, and a huge expansion in the number of law schools and university legal departments. The prime motivation for these ambitious achievements was the Party leadership’s desire to successfully develop a “socialist market economy” and reap the benefits of cooperation with the world community, as symbolized by PRC acceptance into the World Trade Organization.

Yet this turn toward the new and attractive slogan of “ruling the country according to law” was in fact a betrayal of the hopes for a genuine “rule of law”. Some of these achievements did put certain restraints on the conduct of the official government bureaucracy, as imperial law did too, but in neither case did law restrain the ruling power – in our day the Party leadership and, until the twentieth century, the emperor.

Another noteworthy point is the ostensible revival of respect for Confucian philosophy. Until recent years, the country’s Communist revolutionaries, like other twentieth-century Chinese radicals and reformers, condemned Confucius and his disciples as the fount of the “feudalism” that had consigned the once great imperial “Central Realm” to the “century of humiliation” that began, according to Party scriptures, with the Opium War of 1839 and lasted until Communist “Liberation” in 1949. Recognizing from historical experience that the Chinese, like others, are best governed not by coercion alone but by the ruler’s parallel resort to ideology and moral suasion, and seeking to respond to the nation’s sagging faith in Communism, the Party has lately sought to broaden its appeal by invoking a selective version of Confucianism to serve, like the legal system, as another instrument of political control.

The third and present period in the post-1978 contest between “rule of law” and “rule by law” began, as Professor Ye notes, just over a decade ago and moved into high gear in 2012 when Xi Jinping assumed Party leadership and shortly thereafter also became both President of the state and Chairman of the National Military Commission. Although the current era might be characterized as essentially a further application of the principle of “governing according to law”, i.e. “rule by law,” that dominated the second stage, the recent changes wrought in the name of “doing everything through law” have been so distinctive as to warrant separate attention.

Surely this is Xi Jinping’s attempt to complete the process, already well under way, of cloaking Party monopolization of government power with the mantle of legality. It is, of course, a far cry – indeed at the opposite end of the spectrum – from the hope of the long-deposed Zhao Ziyang to largely separate the Party from the government. Three bold constitutional amendments have brought the Party closer to integration with, and almost congruence with, the government than ever before.

The most publicity-generating amendment was the abolition of the two-term limit for the office of the nation’s President. The presidency has gradually come to rival the prestige, if not the power, of the Party General Secretary, for which there is no term limit under Party rules.

This amendment legally formalized congruence at the very top of the Party, government, and military hierarchies.

To ensure legal confirmation of the principle of Party control over the government, the Constitution was further amended to insert that principle into the document’s body, rather than allowing it to rest, as before, in the oft-perceived ambiguity of the Constitution’s preface.

And, to leave no doubt that this principle would be implemented more thoroughly than ever, the third constitutional amendment established a fourth branch of government under the National People’s Congress (NPC). It was designed to consolidate in real life the Party’s control over the other three branches and even over the theoretically all-powerful NPC. The new National Supervisory Commission (NSC) is the most significant innovation yet made in the Soviet government model imported from the late USSR by all other “socialist” states, past and present. It has been endowed with the power to coerce not only all of the Party’s 96 million members but all public officials and others who exercise public functions broadly construed. The NSC builds upon, and shares offices, personnel, and practices with, the Party’s legally unauthorized “discipline and inspection” system, which has played a key role in enforcing the Party’s will among Party members through surveillance, incommunicado detention, and torture so effectively that many targets committed suicide after being summoned. The NSC is considered in fact to be more powerful than the other, pre-existing branches of government – the executive branch including the public security force, the procuracy or prosecution office, and certainly the courts. Although nominally required to report to the NPC like the other branches, the NSC, as the Party’s key legallyauthorized official suppressor of not only corruption but also violations of Party discipline and state law in any respects, is widely thought to be more powerful in affecting individuals and practical affairs than even the NPC and its staff.

In these circumstances, it is easy to conclude that the Party has obliterated prospects for the “rule of law” even while endlessly hijacking its name in order to impose “rule by law.”

How long is the current era likely to endure?

The circumstances surrounding the decisions of Deng Xiaoping to end Chairman Mao’s “class struggle” in 1978 and of Chiang Kaishek’s heirs to peacefully democratize his Leninist-type totalitarian regime on Taiwan during the decade beginning 1987 were very different from those that are likely to prevail for the foreseeable future in twenty-first century China. Yet history is notoriously adventitious, China’s progress under Communism has witnessed many swings of the pendulum, and potential “revolutionary successors” to the ill-fated Zhao Ziyang, prepared to pursue a liberalizing path, amply exist among today’s dissatisfied but suppressed Party elite.

This interview is a part of a volume (in Italian) published by Edizione Scientifiche Italiane and available for purchase here.

Laura Formichella teaches Chinese law at Tor Vergata University of Rome, Law School. She obtained her PhD with a thesis titled “Sistema giuridico romanistico. Unificazione del diritto e diritto dell’integrazione” from Tor Vergata University, where she is a researcher, spending long periods of study at China University of Political Science and Law in Beijing and other Chinese universities. She is the author and editor of numerous publications on Chinese Law and translations into Italian of the most important laws of the PRC. She has participated in numerous national and international conferences as invited or plenary speaker.

Enrico Toti teaches Chinese law at Roma Tre Law school. He obtained his PhD from Tor Vergata University, spending long periods of study and research at the China University of Political Science and Law in Beijing and other Chinese universities. In 2021 he published the monograph Diritto cinese dei contratti e Sistema giuridico romanistica. Tra legge e dottrina. He is the author and editor of numerous publications on Chinese Law and translations into Italian of the most important laws applicable in the PRC and founder of the website Cinalex.it. He is Visiting Professor at the School of Law of the Shanghai International Studies University.