A new paper by Xianqi Peng

A public-private partnership (PPP) is a long-term collaboration between a public authority and a private sector entity, in which the private party delivers products or provides services for the government, receiving a fee from the government or end users. The model enables the state authority to provide at less financial costs the necessary infrastructure to citizens and make projects more efficient by relying on the private sector’s expertise. Since 2014, PPP projects have boomed in China. Until 2024, more than 10,000 PPP projects have been launched, with accumulated investment of 16.2 trillion RMB, according to statistics of the Ministry of Finance. With the high number of PPP projects launched in China, many respective contract disputes have been brought to court. Between 2014 and the end of 2023, over 10,186 PPP cases, including civil, criminal and administrative cases, were handled in total. However, there is a heated debate over whether arbitration can be used for PPP contract disputes because PPP contracts are partly classified as administrative and partly as private law contracts, and the disputes may include administrative actions or contractual matters.

Against this backdrop, this article first examines whether the current legal framework of the PRC excludes arbitration as a procedure for resolving PPP contract disputes. In many jurisdictions, such as the UK, the USA, Germany and Italy, the arbitrability of PPP contract disputes is generally accepted. In China, there is still no specific PPP law to comprehensively regulate the initiation and implementation of such projects. This regulatory gap has resulted in a fragmented framework, with various national ministries and the Supreme People’s Court issuing their own regulations or guidelines to govern PPPs and their dispute resolution mechanisms within their respective administrative and/or juridical authority. Prior to May 2015, several regulations issued by the Ministry of Finance and the National Development and Reform Commission allow parties to settle PPP disputes through arbitration. However, following the enactment of the amended Administrative Procedure Law (行政诉讼法) on 1 May 2015, along with its corresponding judicial interpretation issued by the Supreme People’s Court (最高人民法院关于审理行政协议案件若干问题的规定), PPP contracts were explicitly classified as administrative contracts. These provisions established that PPP disputes fall within the exclusive jurisdiction of administrative litigation, thereby excluding arbitration as a permissible dispute resolution mechanism. However, in November 2023, the Ministry of Finance and the National Development and Reform Commission have introduced a new PPP regulation (关于规范实施政府和社会资本合作新机制的指导意见) and concession regulation allowing parties to PPP contracts to select an appropriate dispute resolution method based on the nature of the dispute. Arbitration is permitted if the dispute arises under private law. This setup contradicts the previous guideline of the Supreme People’s Court under which respective disputes fall exclusively under the jurisdiction of administrative courts. The divergence between the rules of the Ministries and those of the Supreme People’s Court creates uncertainty regarding which rules should apply in cases of conflict.

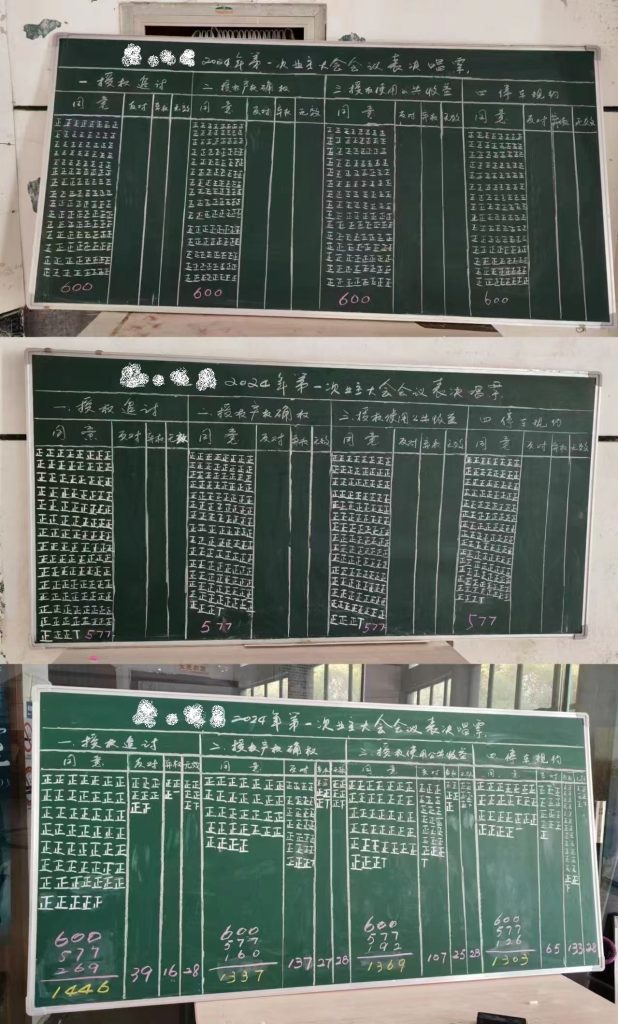

Apart from conducting doctrinal and descriptive analysis, this article develops a comprehensive case study to examine Chinese courts’ attitudes on whether arbitration is used for PPP disputes. Through a key search on the Chinese Case database, a sample of nearly 1,500 relevant cases from January 2014 to December 2023 was collected. A thorough case-by-case review identified 68 qualified cases from different courts, including 4 decisions of Basic-level People’s Courts, 34 decisions of Intermediate People’s Courts, 18 decisions of High People’s Courts, and 12 decisions of the Supreme People’s Court. The data demonstrates that debates surrounding the arbitrability of PPP contract disputes exist across different hierarchies of Chinese courts. Three patterns emerge: Courts of lower hierarchy more often permit the arbitration of PPP contract disputes than courts higher up in the hierarchy. Second, discrepancies in perspectives on the arbitrability of PPP contract disputes arise between first instance and appellate courts. Third, divergent opinions on dispute resolution for PPP contracts also arise among different tribunals within the same court.

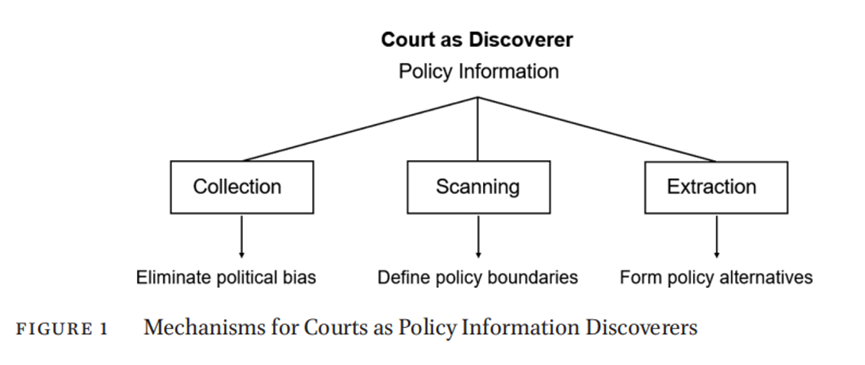

The decisions further demonstrate that the courts adopt three distinct approaches when determining the dispute resolution mechanism for PPP contract disputes:

- The legal nature of the contract determines the dispute resolution mechanism. If the court classified the contract as a private law contract, civil procedures were permitted. Conversely, if classified as an administrative contract, the administrative courts were granted exclusive jurisdiction.

- The nature of the dispute determines the dispute resolution mechanism. Focus is laid on the nature of the dispute itself, specifically, whether they involved the exercise of public authority (administrative disputes) or whether they are rooted in private law issues.

- Party autonomy is priority. If there is a valid court selection provision or arbitration clause, the procedure choice is made accordingly.

Building on doctrinal analysis and the examination of relevant cases, this article concludes that arbitration should not be prohibited for resolving PPP disputes. First, PPP contracts should not be uniformly classified as administrative contracts, and current Chinese law does not expressly prohibit the use of arbitration in such cases. Second, the application of the proximate cause doctrine (in China: 近因理论) is recommended to distinguish between disputes arising from administrative actions and those rooted in contractual obligations. The proximate cause doctrine establishes that when a claimant seeks redress for losses resulting from a breach of contract or tortious conduct, they must demonstrate that the ‘consequences’ of the loss were caused directly by the ‘proximate cause’ of the infringer’s breach or tortious act. This approach would enable a more nuanced and appropriate determination of the applicable dispute resolution mechanism. Third, a pro-arbitration stance should be adopted, one that favors the use of arbitration in PPP disputes while narrowly defining what constitutes an administrative dispute within the context of such contracts. This approach not only leverages the inherent advantages of arbitration, such as neutrality, flexibility, and enforceability, to effectively balance the protection of public and private interests, but also alleviates the concerns of private investors. Winning rates for private parties in administrative litigation are very low. By reinforcing confidence in fair and efficient dispute resolution, this position may encourage broader private sector participation in PPP projects and contribute to the sustainable development of the PPP model.

The full paper, titled “Arbitrability of PPP Contract Disputes in China: Based on An Analysis of 68 Chinese Cases”, is published in the Commercial Arbitration and Mediation (商事仲裁与调解), vol. 1/2025 (in Chinese). Xianqi Peng is a PhD candidate at the Faculty of Law & Criminology at Ghent University, Belgium. His research focuses on international investment law, private international law, arbitration, African law and public private partnerships. He published in journals such as African Studies and Nankai Law Review. He can be contacted at xianqi.peng[at]ugent.be.