A new paper by Ruiping Ye

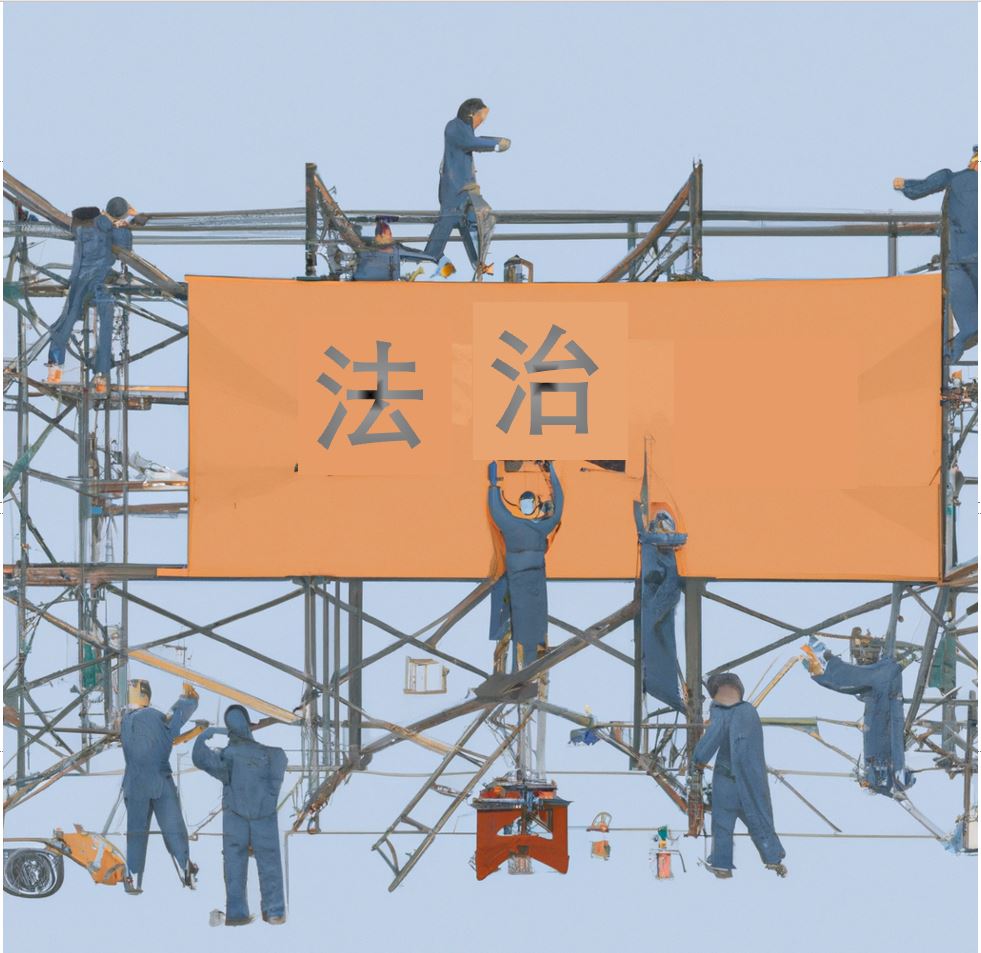

In the past 40 odd years, China has experienced sweeping changes on its legal scene. After the denunciation of law and the destruction of legal institutions during the Cultural Revolution, the country set out to rebuild a legal system when the so-called “decade of catastrophe” came to an end. Since then, legislation has proliferated with law drafting skills becoming increasingly sophisticated, courts adjudicating tens of millions cases annually, and the number of legal practitioners growing from 12,000 in 1986 to more than 651,600 in 2022. The concept of yifa zhiguo (依法治国, literally ruling the country according to the law) was formally propounded in 1997. By 1999, the Constitution was amended to declare that “The People’s Republic of China implements yifa zhiguo and builds a socialist fazhi (法治, rule of law) state”. In 2017, the ruling Communist Party of China established a leadership group on comprehensively advancing yifa zhiguo. A year later, a dedicated yifa zhiguo Committee was established within the Party.

What do yifa zhiguo and fazhi mean in the Chinese context? What do the developments in China’s legal arena signify in terms of China’s progress in achieving the rule of law? Looking past the growing body of legislation and the expanding legal profession, the development of law in China since Reform and Opening began in 1978 has travelled through three stages, from laying down rule of law principles as the foundation, to focusing on ruling by law, and finally current efforts to use law as a means of legitimising the Party’s rule and government actions.

In the early 1980s, Chinese legal scholars and policymakers searched for a governance model that would be different from that of the Mao era. They debated about the rule of law and the rule of man. While much of the discourse did not go beyond the traditional tropes of Confucian “rule of (sage) man” on one side and legalist “rule by law” on the other, some scholars introduced and advocated for principles of the Western rule of law, such as the separation of powers, the supremacy of law, equality before the law and Nulla poena sine lege (no penalty without law). The adoption of fazhi (法制, literally a system of law, legal system), instead of fazhi (法治, rule of law), was a compromise between the two broad camps of “rule by both law and man” and “rule of law”. Considering that at that point in time the country was standing on the rubble of the Cultural Revolution, it was probably pragmatic to prioritise building a system of law, which would provide a tangible framework for the rule of law.

Worth noting is that, despite the use of the term fazhi (法制, legal system) instead of fazhi (法治, rule of law), the 3rd plenary session of the 11th Central Committee of the Communist Party in 1978 and the 1982 Constitution adopted key principles of the rule of law. The 3rd plenary session vowed to “make law stable, consistent and with great authority”, to ensure compliance with law, due independence of courts, and equality of all persons under the law. The 1982 Constitution enshrines all the above principles – the supremacy of the law, equality before the law and judicial independence. The constitutional provisions were skeletal, and the Constitution was (and still is) more of a political manifesto than an enforceable piece of legislation, but the provisions manifested the government’s commitment to the key principles, enshrined in the country’s supreme legal document. A blueprint was drawn, allowing future developments to gradually realize the rule of law.

Post-1989 China curbed the tendency to “Westernise” and reiterated the four cardinal principles for ruling the country, namely socialism, the dictatorship of the proletariat, the leadership of the Party, as well as Marxism, Leninism and Mao Zedong Thought. The Party searched for a theoretical development for the role of law, and the idea of yifa zhiguo was introduced. The 1999 amendment to the Constitution declared the goal of building a “socialist fazhi (法治, rule of law) state”. The two Chinese characters for fazhi (法治) together mean “law governs”, an essence of the rule of law. The official Chinese translation of the phrase is “socialist rule of law”.

Fazhi is also a shorthand reference to yifa zhiguo. The term yifa zhiguo is relatively straightforward; it has usually been translated as “governing the country according to law” or “law-based governance”. A series of laws were passed to restrict government’s administrative powers, including allowing litigation against certain government actions, imposing procedural requirements and limits on administrative penalties and licencing, and providing for state compensation. These laws aimed to correct and improve previous practices that often had no legal basis, yet it was the bureaucracy and not the ruling Party that was subject to the law. At the same time, the idea of yide zhiguo (以德治国, ruling the country by virtue/morality) was highlighted as a principle parallel to yifa zhiguo. Therefore, socialist rule of law was in essence rule by law, wherein law was but one instrument to govern the country.

Since the 2010s, China’s legal reform intensified, as the Party devoted more energy to “construct a socialist fazhi system with Chinese characteristics and to construct a socialist fazhi state”. The Party has become more visibly active in state affairs, increasingly invoking the yifa zhiguo narrative. Significantly, the leadership of the Party was written into the Constitution in 2018, and it has since appeared in a number of amended or new statutes. The 2018 amendment to the 1982 Constitution therefore enshrines the Party as the legitimate ruler of the country and creates the legal basis for its dominant position. Another important change was the legalisation of previously unlawful means of restricting personal freedom. Most notably, the often-criticised shuanggui (双规, two specifics) which had been used by the Party’s disciplinary committee to detain suspected corrupt officials and witnesses extra-legally, was authorised by the Supervision Law of 2018.

China’s 40 odd years of legal development started with aspiration and foundational principles for the rule of law. Post-1989 it developed to become rule by law, and eventually turned towards using law to legally sanction the Party’s rule.

The article “Shifting Meanings of Fazhi and China’s Journal toward Socialist Rule of Law” (draft available here) was published in the International Journal of Constitutional Law, Vol. 19 Issue 5. Ruiping Ye is a Senior Lecturer in law at Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand. Her research interests lie in the areas of comparative law, the Chinese legal system, law and culture, land law and aboriginal land tenure.