Shitong Qiao’s book The Authoritarian Commons: Neighborhood Democratization in Urban China was published with Cambridge University Press in January 2025.

How did you find your way into the world of homeowners in China?

Around 2017, I noted that many of my friends in China, former classmates from Beijing who now work for companies or the government, began complaining about their property management companies. Some deliberated establishing homeowner associations. This group of professionals is generally busy with work and their families, have little spare time and are not interested in discussing politics. But here they came forward, spending a lot of time working on creating homeowner associations (业主委员会,HoAs), to that end actively engaging in bargaining and negotiations that sometimes had them threatened by government officials and property management companies. I wondered, what is their motivation? There is no money to be made from this, and the social capital to be gained is rather small or guaranteed. I realized that the phenomenon is very broad in China.

Why should we care about homeowner associations (HoAs) in China?

Anywhere, HoAs are fascinating – some property law scholars go as far as to argue that HoAs are probably the most important kind of quasi-private organizations, in the USA just as in China. They are like a government in the neighborhoods, an important institution in everyone’s daily life.

In the Chinese case, the emergence of property rights and with it the HoAs are probably one of the most important results of China’s market-oriented reforms. If you compare urban Chinese life in 1978, 1979 to today, the most important and visible consequence is that people now own their homes. For most middle-class families, their apartment is their most important investment. As a popular saying went back then, the three most important things to Chinese families are “儿子、票子、房子 (a child/son, cash, a house).

In addition to the right to own property, the right to associate is a notable development because it is a right of which there are not many, even in today’s China. The other case that comes to mind are the villager’s committees, which were much in the focus of scholars who saw them as potential roots for democracy. While that hope barely materialized, the urban version of them – the homeowner associations – played out very differently. They were not based on lineages, bound into the old cultural traditions of hierarchies and authorities like villager committees in rural China. HoAs are formed by urban citizens who bought apartments from all over China without prior connections. The moment they move into a condomium, they are strangers to one another, but need to learn how to solve their common problems together. In urban residential compounds, one’s social status, like who your father is and where you work doesn’t matter as much. Neighbors had to learn how to communicate with others on an equal ground.

How are HoAs different from other non-government organizations?

“Non-governmental organization” is a broad term, they are not necessarily democratic. Many operate more like corporation: A leader, employees, structures. HoAs make decisions together by voting, and members are volunteers. HoAs also have their own independent source of funding, unlike most NGOs who rely on external funding.

Can you give us some historical context: How did the HoA wave set off and how has the relationship between HoAs and local governments evolved over time?

The background is the urban land reform starting in the 1980s, and the nationwide housing reform in 1984. The first HoA was established in 1991 in Shenzhen. The reason was that some of the residential compounds were still paying the industrial electricity price, which is higher than that for residential electricity. The homeowners realized that they cannot negotiate with the electricity company one by one, and as the entire building was affected, sought to team up with their neighbors. Some of the first homeowner activists I talked to, now in their 70s, explained that there were a lot of different problems in the neighborhood such as with sloppy property management companies, but the companies refused to talk to individual residents. The condominium living structure that emerged in cities in China really forced homeowners to bond.

In 2003 the State Council promulgated the Real Estate Management Regulations, the first national-level law that officially recognized HoAs and gave them a legal basis. One issue debated leading up to this was a mass of complaints of consumers about apartments they bought being defect. Hence, it was the Ministry of Construction 建设部 (now: Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development) which came up with the plan of granting HoAs power to better discipline the real estate developers, to solve the problem of low quality house construction. Housing issues were thus characterized in Chinese media as part of the “consumer rights” movement that was taking off to counter the wave of low quality products and fraud in the marketplace. Back then, the Ministry of Civic Affairs protested during the consultation process of the Regulations, arguing that HoAs might clash with the Residence Committees (居委会), which are grassroots governance organizations inscribed in the Constitution. The response by the Ministry of Construction was to say that they are private organizations seeking to support the sound development of the real estate industry and open to aid the Residence Committees where they could. This somehow settled the tension.

Frankly speaking, there are a lot of overlaps between HoAs and Residence Comittees. HoAs hire their own security guards, cleaning services and so on. There is indeed a direct competition of power between the HoAs and the Party-state (in the form of the Residential Committees) right in the neighborhood.

The key conflict that your research explores is the Party-state’s constant quest for maintaining social stability and homeowner’s interests in self-governing their private surroundings. What are typical cases in which these two positions clash?

There is an incentive for the government to support HoAs, they hope that HoAs can resolve local issues quickly and smoothly. Local governments rely on the HoAs to take care of many things. The street-level government branches (街道办) hope to maintain the status quo, or are even supportive of the HoAs. They call upon on the HoAs for instance when enforcing restrictions during the Covid-19 lockdowns. On the other hand, the HoAs can grow “out of control”. I conceptualize this tension as the authoritarian dilemma.

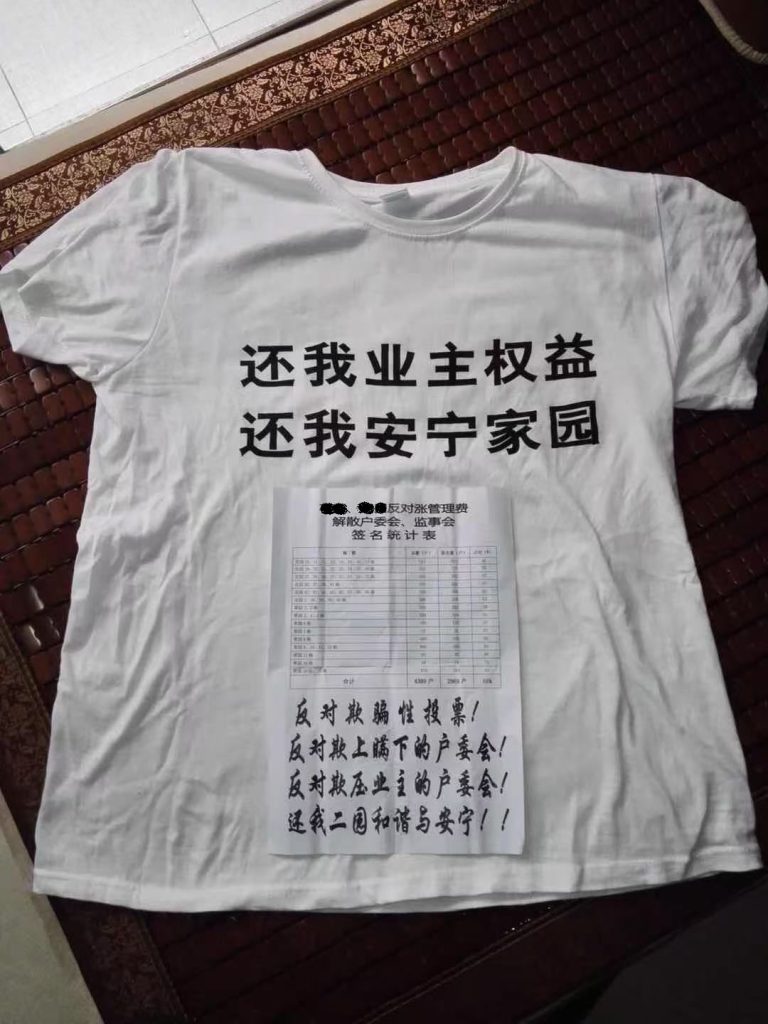

One issue of contestation is when HoAs want to switch property management companies. In one case for instance, protests by homeowners including threats and even physical violence unfolded in a typical middle-class neighborhood in Beijing because of that. The municipal government intervened and cast the homeowners as trouble-makers. Homeowners then created platforms to connect with peers across the city in solidarity. Eventually, a deputy mayor of Beijing backed down and apologized. Such stories happened in quite a lot of neighborhoods where the local government had decided to side with the property management companies rather than grant HoAs requests.

Another type of conflict is the requirement to establish party cells in HoAs. A central Party document encouraged to do so and in some places, especially smaller cities, local branches have translated that into binding rules. For instance, Huizhou required that 60% of a HoA’s board members to be Party members. Most HoA members aren’t Party members, so the requirement isn’t feasible to begin with. A Huizhou homeowner, not a Party member but much supported by his neighbors, contested Party member quotas. He initiated a legality review of relevant local policies at the provincial People’s Congress. He received a favorable reply and managed to force the local government to officially abolish the Party member quotas. His argument was straightforward: He said that neither the Property Law nor the Civil Code mentioned a requirement of minimum Party member quotas, and thus the respective local policies are not lawful.

So the Party’s measures to impact HoAs from the inside largely failed. Are such plans now shelved permanently?

I don’t think the Party center paid much attention before, but in 2017 the CPCCC and the State Council jointly issued a first Opinion specifically addressing neighborhood governance. Now they realized that getting a hold on the HoAs is part of what the Party calls controlling “the last inch of governance”. But can they succeed? Not 100%, unless there is a war-like emergency situation where the market can be totally disregarded temporarily. But even then, I doubt that the Party-state has the resources to exercise direct control over so many neighborhoods in the country for a long time.

Covid-19 was an illustrative example case: Based on my fieldwork, the lockdowns were not realized by placing police everywhere, but by relying on the homeowners to govern themselves. In a case I observed, the HoA successfully refused to place paid security at the gates that would enforce the lockdowns. One of my interlocutors in charge of a HoA said: “A smart leader doesn’t have to do things by himself. A smart leader has people take care of their own business.” Given the limited resources the government has, I don’t think they could directly exert much control. Otherwise the residence committees would have been much better equipped and resourceful. The ongoing fiscal crisis of local governments exacerbates this situation.

Let’s talk about fieldwork in China. You really created a 360 degrees account of the HoA-Party state relationship by talking to and gathering documents from a wide range of parties involved. What challenges did you face in data collection?

I think it helps that I like listening – to people’s stories and problems. Property management is a topic that many homeowners don’t deem sensiitive and that they have something to say and complain about. Getting to know leaders of their networks really helped. It takes Patience and time to build interpersonal connections and trust ,but it doesn’t always work. I ended up joining one potential interviewee on a very long morning run to build trust, but ended up not getting the interview even after 10 kilometres running together. His neighborhood had been in the news, that is probably a reason he was cautious.

A challenge was my affiliation with a university in Hong Kong during the years of social unrest in Hong Kong, people sometimes saw it as sensitive. Later, the affiliation with an American university did not exactly help. Generally speaking, in recent years, people have become much more cautious in terms of who they talk to. That even goes for a formerly not sensitive topic such as property management in residential compounds.

Overall, what role do courts play in neighborhood democratization? At least for the part of administrative litigation, I discovered that a notably large proportion of cases are related to facility management companies in urban residential compounds.

This research really changed my understanding of courts in China. Previously, from my work on small property, I concluded that courts just seek to maintain the status quo. They weren’t exactly at the frontier of social change.

I now found that legal rights and courts actually matter a lot. Courts across China have a huge impact in shaping the fate of HoAs: there are many thousands of case decisions, from both civil and administrative litigation. In one chapter, Rule of Law and Democracy, I explain the big differences regarding the rates of HoAs in Beijing (12%), Shanghai (94%) and Shenzhen (41%). One major reason are courts.

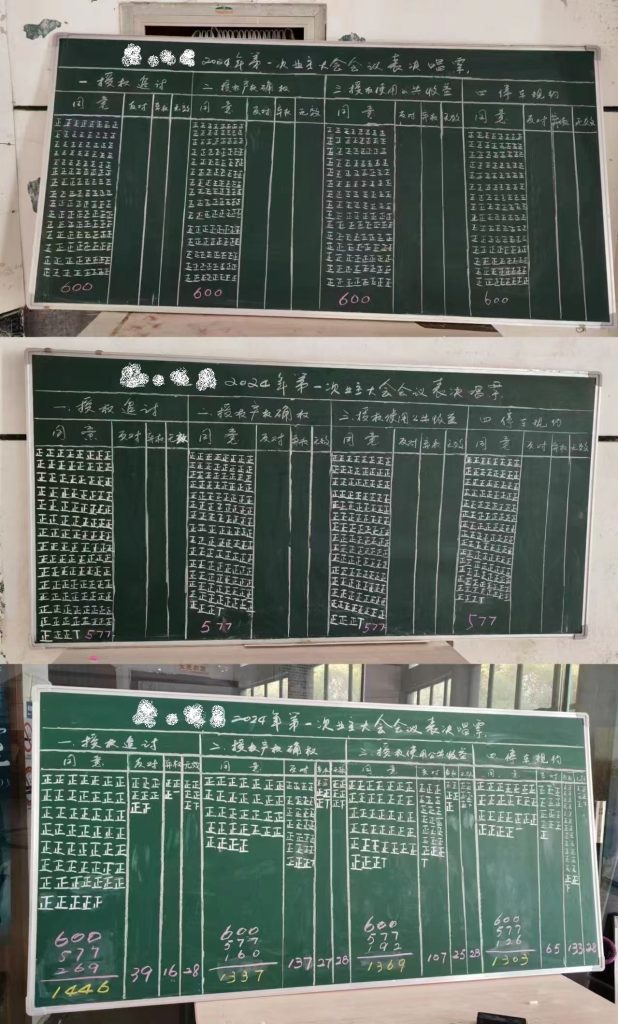

Courts in Shanghai for instance are much more supportive of homeowner autonomy. The Civil Code passed in 2020 imposes stringent requirements on HoAs, for instance that their resolutions are only effective if at least 2/3 of the members participated in a vote. Achieving that is a difficult task: Even just collecting signature from homeowners, often a few hundreds or thousands, is not easy. However, before the Civil Code established this requirement, Shanghai already had a local practice of allowing homeowners to pass resolutions according to the rules they stipulate in their charters. Hence, when the Civil Code came out, in order to not radically break with the established practice, Shanghai courts interpreted the Civil Code provisions very broadly, deciding in favor of homeowners. So Shanghai courts developed a legal reasoning stressing original intent and fundamental spirit of the Civil Code as supportive of private autonomy. The issue has also been brought before the Supreme People’s Court, the local people’s congress and administration, but it was the Shanghai courts that provided a pragmatic solution, demonstrating the unique advantages to local judicial craftsmanship in handling the conflicts between national law and local practices.

Last but not least: What are research questions, suggestions, ideas that you take away from this project?

The first one is a more comprehensive study of the right to associate. So far, it has barely been taken seriously. There are many studies about collective actions, like protests, but I think there is a difference between these and the legal right to associate. HoAs are active in all sorts of things, such as help bargain compensation after the Tianjin explosion in 2015, as our colleague Benjamin van Rooij pointed out.

Secondly, I want to do a comparative study of HoAs across different cultures. How do homeowners resolve problems together? That can tell us a lot about how societies are organized. If anyone is interested participating in this, do reach out to me.

Shitong Qiao’s book The Authoritarian Commons: Neighborhood Democratization in Urban China was published with Cambridge University Press in January 2025. Shitong Qiao is a Professor of Law and the Ken Young-Gak Yun and Jinah Park Yun Research Scholar at Duke Law School. He also holds the title of Honorary Professor at the University of Hong Kong and is a core faculty member of the Asia/Pacific Studies Institute at Duke University. He was previously a tenured professor at the University of Hong Kong, a Law and Public Afffairs (LAPA) fellow at Princeton University, and the inaugural Jerome A. Cohen Visiting Professor of Law at NYU.