A paper by Daniel Sprick

Calls for and attempts to rendering the Chinese Constitution meaningful in judicial adjudication have officially stopped in 2008, when the decision by the Supreme People’s Court based on the Constitutional Right to Education of Qi Yuling was withdrawn years after it had been made (find the somewhat odd story about a student who has stolen another’s identity to enter college and the ensuing case here). The move has made it clear that the authorities do not wish that the Chinese Constitution serve as a legal basis for judgments. However, judges continue to invoke the Constitution, if less as a direct legal basis, but more so in the reasoning part of their decisions. As judgments by courts from all over China were gradually being entered into an open-access database, Daniel Sprick seized the opportunity asked: If it is not permitted as legal basis, in what ways does the Constitution still play an authoritative role in adjudication?

The quest for today’s functions of the Constitution in the daily adjudication work of local judges appears even more significant when considering the growth of a net of legislation that offers judges alternative legal sources to choose from. A law laying down the Right to Education for example was not yet existent when the controversial Qi Yuling case was first decided on.

For this study, Sprick looked at case groups invoking the Constitution that concerned disputes over citizen’s duty to support elderly parents, land administration or the right to work. Cases, where the Constitution is being referred to due to a lack of lex specialis particularly emerge from disputes over land administration. However, in most cases Sprick found in the database, invoking the Constitution would indeed technically not have been necessary- other laws are the decisive base. Nevertheless, judges are “seeking a higher authority in order to frame a more compelling argument and exhibit an understanding of the constitution as a programmatic document that links the CCP’s policies with the state law.”

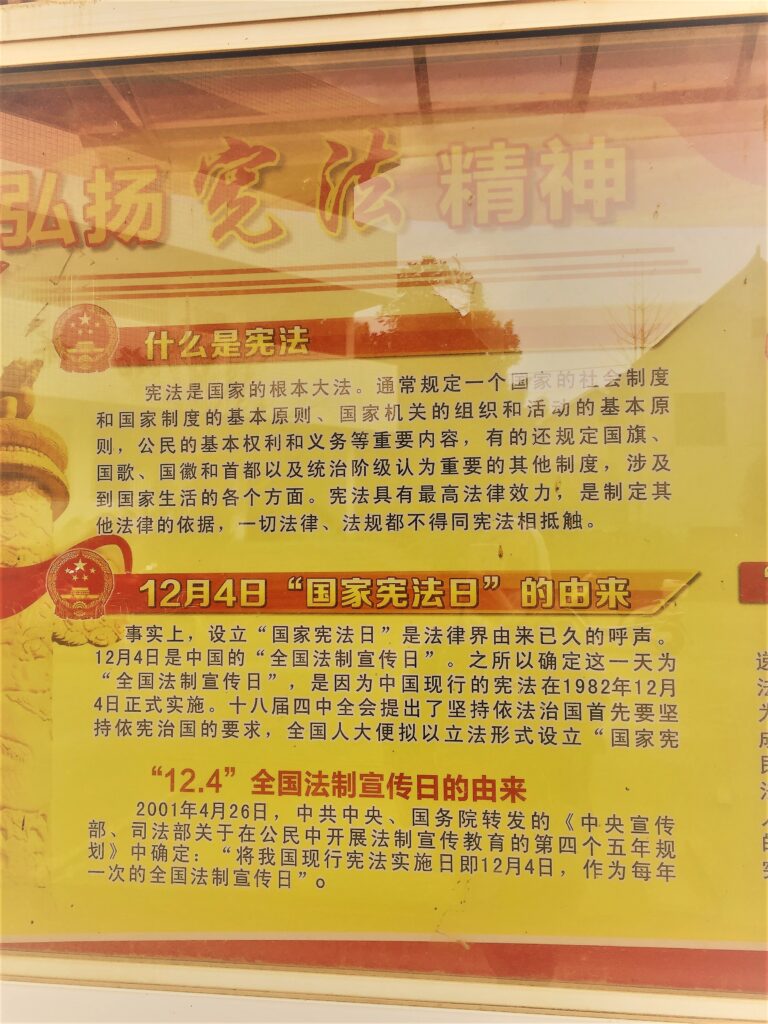

Apart from functioning as a link of law and CPC policy, he further finds the Constitution as useful tool for judges working on tort law cases. More precisely, the right to work is being referred to when interpreting relevant statutes, stressing the rights of seniors who were working even though they had reached the retiring age: “the use of the constitution demonstrates that the courts are here filling a legislative gap for the purpose of social justice.” Given the propaganda campaigns calling the general public for the “implementation” and “ardent study” of the Constitution in the aftermath of its amendment in 2018, Sprick’s research appears as relevant as ever.

Find the PDF here: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3333958

Daniel Sprick is a Research Associate at the Chair of Chinese Legal Culture at the University of Cologne, where he teaches a variety of courses on Chinese legal history and Chinese economic and commercial law. He was awarded the Hanenburg-Yntema Prize for the best European thesis on Chinese law in 2008. He received his PhD from the East Asian Institute at UoC on the limits of self-defense in Chinese criminal law. His research has focused on Chinese criminal law, competition law, law and society, legal theory and judicial reforms in China.