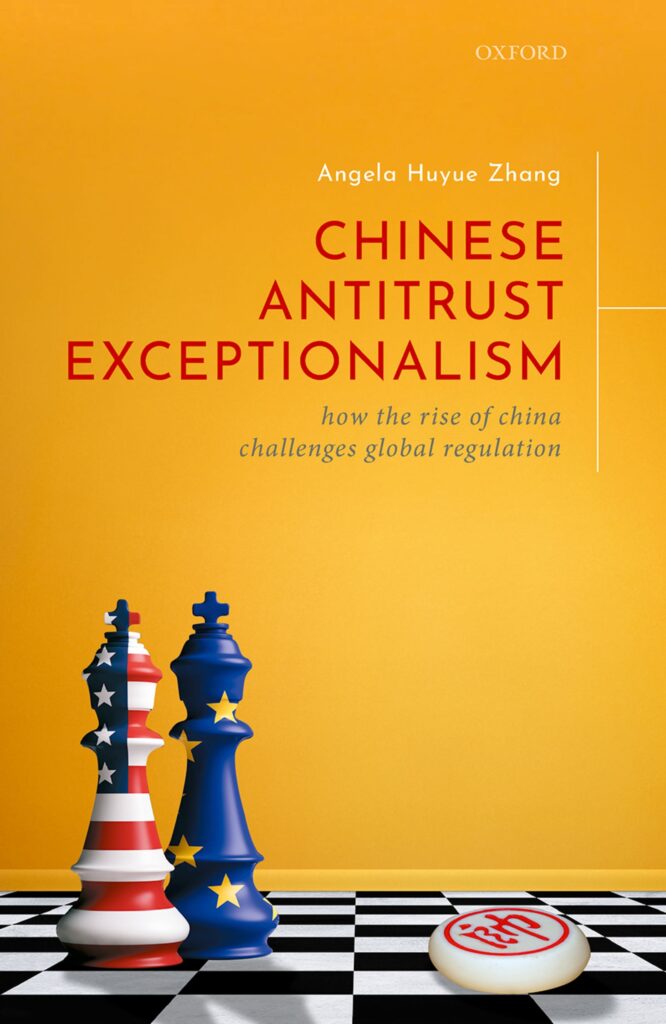

Opinion by Angela Huyue Zhang

In recent months, Chinese antitrust authorities have ramped up their efforts to rein in Big Tech firms such as Alibaba, Ant Group, Meituan and Tencent. These enforcement actions were all launched after Jack Ma’s controversial speech criticizing Chinese financial regulation last October. Many have therefore speculated that there are political motivations behind China’s crackdown on Big Tech. While Ma’s speech may have been the tipping point, there have been long-standing economic, social, and industrial policy issues that merit the government’s action. In fact, Beijing’s recent efforts to strengthen antitrust regulation in the tech sector could facilitate a larger goal of the Chinese government: to become a technology superpower and achieve self-sufficiency, removing reliance on the West.

In this regard, how China handles antitrust law offers it a distinct competitive advantage, particularly compared with the U.S., which is also grappling with how to handle tech giants. Even though efforts to rein in companies such as Google and Facebook have gathered momentum, the U.S. government has significantly less leverage than China when it comes to antitrust law. Indeed, any U.S. legislative changes will take years to enact, and existing antitrust cases brought against Big Tech also face uphill battles in U.S. courts.

China shares some of the same concerns as the U.S. over increasing market concentration in the tech sector. However, Chinese big tech companies do not thrive because they develop innovative technologies. Rather, they build smart apps that make it easier for consumers to connect with merchants. Even though China has emerged at the forefront of e-commerce and digital payment, Chinese Big Tech still owes its success, to a large extent, to China’s vast consumer market.

Despite their sophisticated software development capabilities, companies such as Tencent and Alibaba have yet to develop foundational technologies. China’s fragility in technological innovation was clearly exposed during the Sino-American trade war—the operations of national champions such as ZTE and Huawei could be easily interrupted if the U.S. government withheld the supply of key components such as semiconductors.

China’s weakness in technological innovation explains Beijing’s recent emphasis on achieving technological self-reliance and its desire to push Chinese tech giants in this direction. Since China is the only country apart from the U.S. to have Internet giants, these tech firms are in a good position to develop digital technologies for the country. In some ways, Chinese tech giants have responded to the government’s call. Tencent has promised to invest $70 billion in new digital infrastructure. In 2019, Alibaba unveiled its first chip to power artificial intelligence. Baidu is betting heavily on driverless cars.

But Beijing wants more. Its intentions were clearly revealed in a recent editorial by the People’s Daily, a Communist Party mouthpiece, which chided tech firms for investing in the “community group-buying” market. The commentator instead urged Chinese Internet giants to forge ahead with higher ambitions, such as advancing technological innovations to clear China’s bottleneck in the intensive Sino-American rivalry, rather than focusing on selling cabbages.

In the meantime, antitrust law enforcement gives Beijing significant regulatory leverage to push its tech firms in the direction it desires. Antitrust law grants the central government strong sanctioning powers, allowing it to impose anything from astronomical monetary fines to severe structural remedies. The Chinese antitrust regulator also possesses vast administrative discretion while being subject to little judicial oversight. Furthermore, Chinese antitrust law enforcement is spearheaded by a central ministry that follows the central government’s directives carefully.

As Chinese tech giants have amassed significant market power, they have become vulnerable to antitrust regulatory attacks. And just as U.S. and EU regulators are tightening their antitrust scrutiny over Big Tech, the Chinese antitrust authority also has perfectly legitimate reasons to do so. The regulatory vulnerability of Chinese Big Tech, in turn, facilitates their cooperation with Beijing to help the latter achieve its goals, be it in antitrust or other industrial policy matters. Thus, Chinese Big Tech can and do align their business development strategies with the government’s industrial policy as a form of self-protection.

Indeed, the Chinese government views antitrust law as a powerful multipurpose tool not only for tackling monopolies, but also for achieving a wide variety of policy objectives, such as maintaining price stability, industrial planning, and trade and foreign policy. Thus, the absence of checks and balances in Chinese antitrust enforcement, supposedly an institutional weakness, could actually be a strength for Beijing as it pushes tech giants and the country toward achieving technological self-sufficiency.

Angela Huyue Zhang is the director of the Center for Chinese Law and Associate Professor of Law at the University of Hong Kong. She is the author of Chinese Antitrust Exceptionalism: How the Rise of China Challenges Global Regulation, published by Oxford University Press in March 2021. This opinion is an abridged version of an opinion that was first published with Fortune: China antitrust: How regulation helps it compete with the U.S. | Fortune.